I’m perched on the windowsill in my study at home in Bethesda. The window is open. I stare outside into the distance and have a déjà vu feeling. As I squint trying to penetrate the fog of memory, my imagination blends with what I see: a uniformed battalion of school boys, from grammar school through high school, a type of pseudo harmless army marching on a rectangular field of grass. The boys march in step to the music of a military band, and then stop abruptly, after hearing the command, “BATTALION, HALT!” I don’t actually hear the music or command from my windowsill, of course; it’s in my mind, loud and authoritative. The music is inspiring. Now I hear “LEFT FACE!” and see everyone turn to the left in unison, military style, their collective heels making one clear snapping sound. I don’t see any swastikas; these are American boys. The young boys in the battalion stand motionless at attention, clutching M1 rifles by their right sides, facing parents and friends sitting on benches across the field. Most look proud, some bored, one or two look angry, or perhaps discouraged.

I am unbearably hot on the windowsill and so I roll up my sleeves. It helps me feel cooler, but I’m dizzy and anxious. That’s it: I’m anxious. I try to think why. It’s been more than a year since I’ve retired from almost 50 years of science. I am no longer pressured by deadlines and obligations to keep my laboratory running smoothly, or students satisfied and progressing in their fledgling careers, or lectures to deliver, or manuscripts to write. And yet anxiety poisons me as I stare out the open window into the fading light in the distance.

Suddenly I see a boy on the field fall flat on his face: plop! He is about 12 years old and lies beside the other boys aligned in perfect rows. No one budges. A boy from the back comes and drags the prone body off the field. I remember being one of those boys standing in rows, wanting to help but not supposed to, scared of fainting myself. “Wiggle your toes,” they used to tell me, “that will stop you from fainting. It helps keep the blood circulating.” I remember wiggling my toes all day at Black-Foxe Military Academy, scared that I might faint during the Friday parades. I loved my toes then, little saviors; now, not so much. They feel weird today, like they’re swollen and not very obedient; peripheral neuropathy, I think, but maybe just discomfort from stenosis and surgery in my lower back. I am 70 years old on the windowsill, my body that is. But looking back, I’m…well…I’m many ages. At the moment, time is an accordion and I’m the musician.

I see three companies of boys in the battalion standing at attention; each company, Alpha, Bravo and Charlie, comprises two platoons and is led by a commander, a Captain with four gold stripes on each arm. I recognize these company commanders. Van is standing with dignity as Captain of Bravo Company. My friend Van, the most thoughtful person in my high school class, who told me that there is no such thing as absolute truth because one can always wake up the next morning being uncertain of what was apparently definite the night before. It made sense. Truth changes, with time, with experience, with so many things.

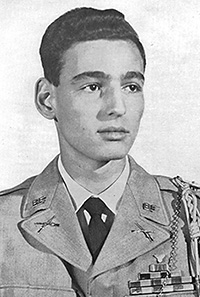

Joram in his Black Foxe uniform

I’m not standing among the troops during the parade. Rather, I am at the opposite end of the field facing the battalion. I’m the Major, the executive officer on the staff of the battalion commander, the Lieutenant Colonel, the head honcho. He has six stripes on each arm. They must be heavy, all those golden threads on the dress uniform, all that presumed responsibility. I am standing rigidly behind him as he barks orders to the battalion. I’m decoration, with five stripes on each arm but no one to command, and so my stripes are not so heavy. At Black-Foxe the Major is a showcase. The Sergeant Major stands next to me. I can’t remember his name, but it doesn’t matter. I am standing straight as a cornstalk gazing at the battalion and band, doing nothing but looking pretty, thinking about my upcoming tennis match and worrying that I messed up on the history exam that afternoon. I’m a senior in high school. I’m not a military type, not then, not now. But neither am I a rebel; too bad perhaps. But that’s the way it was, still is, on the windowsill.

Dusk darkens the distance and the parade fades from view. I squeeze the accordion of past time, bringing me to the present. My back begins to ache. I look out the window and Van appears again, this time with a gray beard and a ponytail, a man I never would have recognized if I didn’t know he was my friend from way back then. He walks along the driveway to his home with his dog in beautiful Yalakom valley, off the grid in British Columbia, near Lilloet. I’m in a rented car from Vancouver with Lona, my wife of 41 years. I haven’t seen Van in 52 years. Some say that’s a long time. I don’t know if I agree. I study evolution where serious intervals of time often begin at a million years. Neither Van nor I is wearing a military uniform. Our lives have diverged, yet here we are, together, with no distance between us. Impressive how time can be contracted and stretched, one way and the other, back and forth.

“Joram,” he says, “I can hardly believe it. You really came.”

“Absolutely. It’s great to see you again. Finally.”

At the moment, time is an accordion and I’m the musician.

I didn’t know what to expect from my friend, gone hippie, with the courage and imagination to live an alternative lifestyle. I doubt that Van knew what to expect from me either, his conventional high school friend, a scientist from the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, those huge U.S. government biomedical research laboratories. Perhaps he would find me a stuffy bore, a pedant to tolerate for two days. Van invents the rules of life; I live within the bureaucratic morass of government. He plants vegetables and lives by the rhythm of the sun; I buy my food, punch a clock and keep working after that as well, before I retired anyway. But none of that really matters at this moment. We’re two men just turned seventy, both with beards, I rather bald, Van with a full head of hair. Lucky bastard!

We go into Van and Eleanor’s house for a visit of barely two days. It’s not much time, but considering we’ve not seen each other for more than half a century, it’s an eternity. We see their vegetable garden kept moist by the overactive sprinklers and their storage place for winter food; we enter the hot house where turkey chicks are maturing to become tasty meals. Van stoops to care for the young ones, merging present love and future needs. A cock struts freely, owning his universe within the fenced in yard. I wonder which fences Lona and I crossed to reach this far-off, independent society. We reminisce about Black-Foxe, eat the homegrown vegetables, fresh eggs, turkey, Eleanor’s jam, and goat cheese from the neighbors, go for short walks in the green paradise, spot an eagle atop a tall tree, just a white speck, free. Listen to the crickets, or so I’m told. My hearing is fading and I can’t hear them. Age depresses and scares me. I have so much more to do.

Van’s daughter, Robin, comes by with her Cuban husband, Camilche, and their 6 month-old daughter, Osha, to spend the day with us. Continuity is independent of lifestyle. It’s all so natural, everyone together, with no apparent stress. Visions of our sons and their families living far from us, Auran in San Francisco and Anton in Toronto, flash in my mind, and I think about space and am comforted by the idea that gravitational attraction operates through vast distances. Another neighbor comes by to do her laundry in Van’s house. “Hi,” she says to all of us. “I won’t be long.” Neither Van nor Eleanor raises an eyebrow. The community is one, a colonial existence. I think of our large home in Bethesda where we have lived for 35 years. A fence surrounds the property and we barely know our neighbors. The thought that I am used to our way of life, more private and self-contained (although not self-sufficient), suddenly throws me back to the present. I enjoy the luxury of a blank mind for a few minutes.

I now peer into Van’s house from my windowsill and see his living room lined with books on shelves; there are more books in the adjacent study, where Van produces his annual journal, Lived Experience. There are books on art, philosophy, travel, healing, you name it, they’re here, and I want to read them all. I realize that I never sent him a copy of my book on evolution and genes and decide to send him one when I get home, where I am now, on the windowsill. Every library needs a book that is never read!

Van shows me the deck outside his study where he often writes looking out onto the mountains. Another common bond: we love to write. He tells me that he is working on an autobiography and I imagine he has much to say, about leaving the United States – his country and family – for British Columbia, starting a commune, owning several book stores, teaching literature, raising Robin, becoming a recent grandfather, sustaining himself and Eleanor off the land in a community of unrelated kin, where water can be thicker than blood. I think about my own memoir in progress, still bits and pieces. It seems conventional: formal education, career path, and few risks taken.

It’s not the external environment that ultimately rules one’s life.

I hear Van say, “Keep writing. Truth interests me more than fantasy.” I wonder what he imagines is the difference between truth and fantasy, between events and the experiences inside one’s mind; for me one cannot exist without the other. I think of his journal and the name perplexes me. Aren’t all experiences lived? But, I know what he means; celebrating life. I’m happy to have published a poem and short memoir in Lived Experience in the last two years; it’s another bond between us.

Van in his Black Foxe uniform

As evening encroaches, Van and I touch upon the lives we’ve led. He talks of Black-Foxe in Los Angeles remembering names and events that I strain to recall, mentions his lawyer brother still in Los Angeles, his college days at UCLA, experiences in Cuba and elsewhere, past commune and present sequestered life in the close-knit community I’m visiting. His life experiences are foreign to me, but yet I feel they overlap mine in some ways, like coalescing water from two broken glasses spreading on a tabletop forming one puddle. We had the same high school teachers, the same worries about final exams and concerns about life after high school. Our parents loomed as major figures during our adolescent years. Differences in details melt with time. When our lives diverged, I focused intensely on science and career, while Van found his identity by traveling and experimenting. As I listen to his tale I imagine freedom with envy. I think how lucky I am that his life enriches mine by our friendship. Perhaps that’s the way we fill the voids of our incomplete lives.

“It’s big industry, cutting down all those trees,” he says.

“Around here?” Lona asks.

I’m intrigued. I hear a note of discouragement mixed with anger in Van’s voice, all well controlled. He continues.

“Can’t win on the long run. I’ve spent so many hours fighting it. It’s a relief to forget about all problems and about our community meetings for a couple of days.

Being off the grid is no different than being in the big city, I think: problems, challenges, frustrations, and disappointments amidst satisfactions. It’s not the external environment that ultimately rules one’s life.

Well, not entirely. Van told me of the nearby fires in the hills across the river causing him to evacuate last summer. And now, while on the windowsill, I just heard by email that their valley is filled with smoke and they’re on evacuation alert again. There’s no escape from planet earth, on or off the grid. I remember last winter being trapped in our house in Bethesda with all its modern conveniences, snowfall records broken, driveway clogged and impossible to travel, power out, no electricity, no water, only cell phone service. Being at peace is being dead. I don’t like the choice.

Eleanor offers us hot tea, which we happily accept.

I use my laptop to show Van digital pictures of my home, my art collections, my two sons, Auran and Anton, and five grandchildren. I’m concerned that my posh existence in suburbia will distance him from me, but it seems not so. We’re friends, after all; the rest is window dressing, like a military rank.

The future is as ephemeral as the past and only becomes real when we make it so.

As we talk I’m struck about how we imagine our lives as single stories, but there seems little truth in that. We change uniforms easily, in our minds if not in fact, sometimes from one year to the next, or day-to-day, or minute-to-minute. We even wear different uniforms simultaneously, as I do now: research scientist, aspiring fiction writer, art collector, friend, husband and human being, trying to resolve the layered contradictions called a life. Seeing Van again makes clear that memories are more than footprints embedded in the past; they are dynamic, reborn with every recollection. Fossils they are not. Nor are they photographs, but rather movies with evolving plots, modified in different contexts, seen through different lenses under different circumstances. Van changes from my high school friend and Captain of Bravo Company with ambitions of greater military heights to a broader man in a softer cloth, a teacher and a leader of a different kind. I no longer see my past confined to scientist confronting nature’s secrets and striving to excel, but a past that prepared me to cross borders and explore new pastures. And then the unexpected miracle: the memories transform into the raw material for the narratives we are yet to write.

Two days pass quickly, we hug, promise to see each other again, and maybe we will. The future is as ephemeral as the past and only becomes real when we make it so.

I am thrust forward to the present moment in Bethesda, on the windowsill, where Lilloet is just a name, a dot up north somewhere in the wild. It’s nighttime now and outside black nothing, so I turn my head and gaze inside my study. The bright incandescent lights defy the natural cycle of the day. The room is filled with Inuit sculptures on shelves and stands, African tribal staffs and figures, oriental rugs on the wooden floor, prints and drawings and paintings on the walls, some bought and others made by Lona and my sister and mother. Overcrowded? Certainly. It often embarrasses me as a mindless accumulation, and for what I ask? Then there’s my desk, computer, science and literary journals, research manuscripts, half-written short stories, essays and a partial novel I have yet to finish, all trappings of an active life. Death alone wipes clean the smorgasbord, the commotion and dead ends that fill one’s space. The Inuit sculptures representing shamans caught red-handed switching between life forms catch my attention, for I, too, am in transit from scientist to writer, trying to insert a new piece of the puzzle to fill the gap and enlarge the image.

My eye is drawn beneath the shelves to the closed door of a cabinet which hides a copy of my doctorate thesis, my book on gene sharing (a term I coined from my research), books and journals containing review chapters I’ve written, and a few reprints of my scientific research articles; in short, a snapshot of my scientific life. But I’m retired now, an emeritus scientist, although my finger is still in the scientific pie. All those years of effort look to me at this moment like a fleeting blur seen from a speeding train.

It’s late and I’m sleepy on this windowsill. I close my eyes and rest.

Morning light and a cool breeze through the open window awaken me and I look outside again. The clouds cast dark planes of shadows save for a narrow stretch of brilliance not far from Lilloet. I see our rented Nissan heading south to the Friday Harbor Laboratories at the University of Washington on San Juan Island. Before I have time to blink we cross the U.S.–Canadian border and then we’re on the ferry, like 47 years ago when I was a graduate student from Caltech coming to spend a summer doing research at the marine laboratories. I stand at the bow of the ferry with memories reawakening: the sense of freedom and adventure, the cold wind tinged with a splash of salt water, the unspoiled islands of Puget Sound, the jellyfish below the surface of the water impervious to the passing ferry (or so it seems to me), the white caps popping up randomly signaling unseen drama, life and death beneath the water’s surface. There’s personality in this place, a characteristic vibrancy mixed with history. Like memories, seeing for the second time can be more than seeing twice. Maybe my interest in science is more alive than I thought it was visiting Van.

We arrive at Friday Harbor and take the short drive through town to the laboratories. As when I first came that summer long ago, I’m a 23 year-old graduate student again, yearning to learn. The student and research laboratories, dormitories, cabins, cafeteria, the scattered trees and rocks, the deer, foxes and raccoons roaming freely, the lure of the teaching and research laboratories reappear from yesterday. Colorful sea anemones, starfish, sea urchins, tunicates, sea cucumbers, barnacles, the amazing sea pens and sea feathers, looking more like plants than animals, worms, shrimps, scallops – the rich diversity of marine invertebrates and algae in the holding tanks – dazzle me, as they did before. The trickle of running seawater and the indescribable smell of a marine laboratory bring nostalgia. My sea legs sway when I spot the special boat for collecting different species moored at the dock, as if it’s waiting for my return. My arms feel strong again when I see the small boats I used to row while waiting for my experiments to cook that summer many years ago. I am comfortable in this place, like a hermit crab that finds a shell that fits. I understand this way of life, the scientists, the challenges and small victories; it’s who I am, my identity.

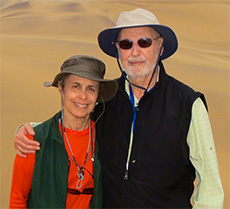

Lona and Joram, artists and explorers

Or is it who I was? I’m here for three weeks as a novelist, a Whiteley scholar, not a research scientist. Forty-seven years ago I was a bachelor; now Lona accompanies me to make art: prints, collages, whatever sparks her interest. Marine invertebrates inspire her and I will look with envy and much pride at her remarkable accomplishments in these few weeks, another instance of my growing by association. We do not define our lives alone; we are each other to some extent.

I go to my assigned desk in the Whiteley Center. Other scholars – writers, scientists, economists to name a few – work quietly in other rooms. I see the town of Friday Harbor across the water past many yachts in the harbor. The ferry blows its horn as it comes and goes; seaplanes skim the water as they land and leave. I connect my laptop to the Internet, that vital link to everywhere, pull out my notes, and prepare to write. The plan: to write a novel!

Just the thought jolts me back to the windowsill, where I’m sitting, watching, thinking. I’ve never written a novel before. It’s overwhelming. I remember Van’s advice just days ago. “Don’t write a book,” he said. “Just write whatever comes to mind. Let it flow. The connections will emerge naturally.”

I look out once more from the windowsill and there I am, sitting at my desk in the Whiteley Center. “Ok,” I tell myself, “I’ll write disjointed scenes that spring to mind, scenes that might enlarge and fuse into the novel I have in mind.” I’m uncertain how I might eventually connect these scenes, if at all. Perhaps Van is right and they will grow together by themselves. The uncertainty mirrors the mystery of life: what directs our choices and steers our contorted paths, how much chance, how much design? And what is this novel I’m writing? It’s a fantasy; science fiction mixed with truth, about a scientist, thinly veiled as me I fear, studying jellyfish, which I have done. It seems I’ve come full circle, from a student at the Friday Harbor Laboratories with a love of nature who takes a life-long journey in the world of science and then returns much older with memories mixed with fantasy. But that’s not all; I also have new thoughts and dreams. The journey is never circular; it meanders here and there as it goes around. I am meandering now, in transit between the worlds of science and writing. The adventure continues.

A “Hello!” startles me. I look up and see Arthur Whiteley, my research mentor for the summer 47 years ago, supported by a cane, eyes alert, impressively fit at 93, an emeritus professor still entrenched in science, reading the scientific journals, going to seminars, discussing research with other scientists. We talk. He tells me how much he misses his wife, Helen, now dead for 20 years, and shows me photographs of her in the Helen R. Whiteley Center. Yes, that’s right: her center, not his.

“We celebrated the tenth anniversary of the center last month,” he says. “I loved creating this multicultural retreat.”

I met Helen once, a fine scientist who understood that creativity shuns artificial fences. The center is a deserving tribute to her, but that’s not my thought as I sense Arthur’s pride in his creation. I think of an effacing man, a modest man, a man who doesn’t self-promote. Yet, here once again, I see how life extends beyond one’s skin: Arthur lives in Helen and she in him. And how unexpected that Arthur’s fine accomplishment, the Helen Whiteley Center, flowed from love and not ambition, how there’s growth from mourning and new life from death. I think of Lona and her prints – wonderful works of art – my pride in that, her work, not mine. I think of Auran and Anton, and my grandchildren, my genes dispersed. And then I think of Van. Although far off my traveled path, a part of me resides in Lilloet, and perhaps a part of him with me. And so it goes, whether we acknowledge it or not.

“Would you be willing to give a lecture to our students and staff on your research, although I know you’re here to write?” asks Arthur.

Of course I would, with pleasure and not just to be polite. I see my past and present merge and grow, both alive and well, and this gives me confidence and makes me happy.

My lecture given, some scenes of my future novel written, my trip to British Columbia and Friday Harbor over, I jump off the windowsill and go to my desk and write these thoughts. I must complete this essay, finish that novel, make more friends and cherish those I have. Perhaps I’ll return to the windowsill at a later date, but there’s more to do right now before I play again a melody with the accordion of time.