As a scientist, writer and collector, Joram continues to explore the world around him.

Scientists develop hypotheses – possibilities – to bridge gaps in the narrative between the known and the unknown. We look at the specimens and data we collect and try to tease out meaning, examining what we have, questioning what we might be missing, and trying to reconcile the two. We do this in hopes that others will build on the work we have done, thereby modifying and advancing our views and conclusions. In a nutshell, this describes my life as a basic scientist.

I spent close to 50 years in science as a molecular biologist and eye researcher, first at Caltech as a graduate student from 1962 to 1967, and then at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In 1981, I founded the Laboratory of Molecular and Developmental Biology at the National Eye Institute and served as its chief until 2009, when I closed my laboratory and became a Scientist Emeritus, an NIH position I hold presently.

Late in my science career, I thought I might eventually move from science to storytelling in the more traditional sense – writing fiction, essays and memoir. Having much to learn about writing fiction and non-science, I took workshops at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda in the evenings and weekends, letting my imagination roam free. What a challenge and thrill it was to explore this new adventure in creativity!

In 2009, after a lifetime of publishing scientific articles on my research followed by a book on evolution and genetics, Gene Sharing and Evolution (Harvard University Press, 2007), I closed my lab and focused on writing fiction. My first publication was Jellyfish Have Eyes, a novel blending imagination with my past research experiences in jellyfish vision in the mangrove swamps of Puerto Rico, which I consider a highlight in my years of science.

Since then, I published a memoir, The Speed of Dark, about my childhood, science, and other interests, two collections of short stories, a collection of brief essays based on my blogs (many on this website), and two other novels, Roger’s Thought-Particles and Regina’s Imagination Universe. Together, the three novels make a trilogy with Jellyfish Have Eyes: Science Fantasies.

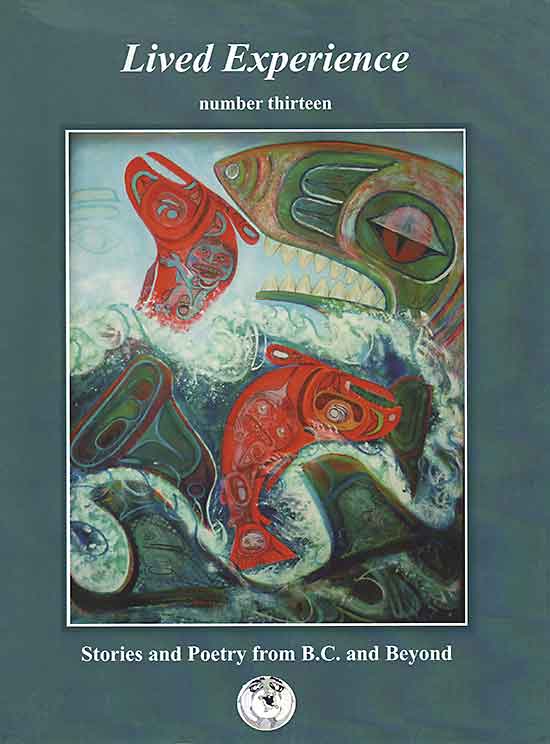

From my parents – my father, Gregor Piatigorsky, who escaped poverty and pogroms in Russia to achieve international fame as a cellist, and my mother, a multi-talented heiress of the French Rothschild banking dynasty and artist – I inherited a love of art and propensity for collecting it. I am drawn in particular to Inuit art, fascinated by its origins in the frozen Arctic, diverse artistic voices, tactile textures of the sculptures, and mythology, especially concerning the shamanic transformations. It took me a while to recognize the link between these transformation pieces with my interest in evolution, which impress me as artistic representations of the continuity within the animal kingdom, humbling the idea of our superiority, and reflecting a deep and unwavering equality and respect for all species.

They also raise more questions than they answer, as is so often the case with art, science and life. It is our work then to keep asking questions as we move into uncharted waters, forming and reforming the stories of our own evolution from the fragments of answers we find. Some dispatches from my journey are posted here on my website.

My wife, Lona, of 53 years at the time of writing, our two sons, Auran and Anton and their wives, and five grandchildren have been my greatest gifts and make my journey in life worthwhile.