My last blog, “Wrapping Up My Memoir,” announced my memoir in its final stages.

Reconciling my science career with the background of my artistic family is an important theme in the memoir. Collecting Inuit art was an activity, apart from the science itself, in which I expressed my bent for art, which is represented in the memoir. Collecting can be creative, as science can be, and has many facets. I consider “repetitions” a challenge to collectors that I considered, but didn’t include in the memoir. Thus, I call such relevant, excluded ideas, leftovers.

By repetitions, I include close similarities – works on the same subject or theme or image as what was done before, but not exactly the same, not imitations, but a piece closely related to a predecessor, testing different viewpoints or possibilities – art a critic might diminish as derivative.

Like other collectors, I gravitated towards Inuit sculptures that appealed to me, in the same way that I did research on topics that intrigued me. Of course, I also considered intellectual interest – what does the art represent and who made it – as well as its esthetics and artistic appeal. Similarly with science, the potential intellectual possibilities were tethered to the extent that a project aroused my curiosity in an unexpected fashion, suggesting there might be something important and different to learn, such as, for example, what’s a scallop or jellyfish eye like, and how it might add to what we already know, or at least make us reconsider our views?

The conundrum of what science projects to do is analogous to what art pieces to add to a collection, or even more difficult, how many similar pieces to collect by the same artist? In short, what’s the role of repetitions in collections, or most interesting, in creativity?

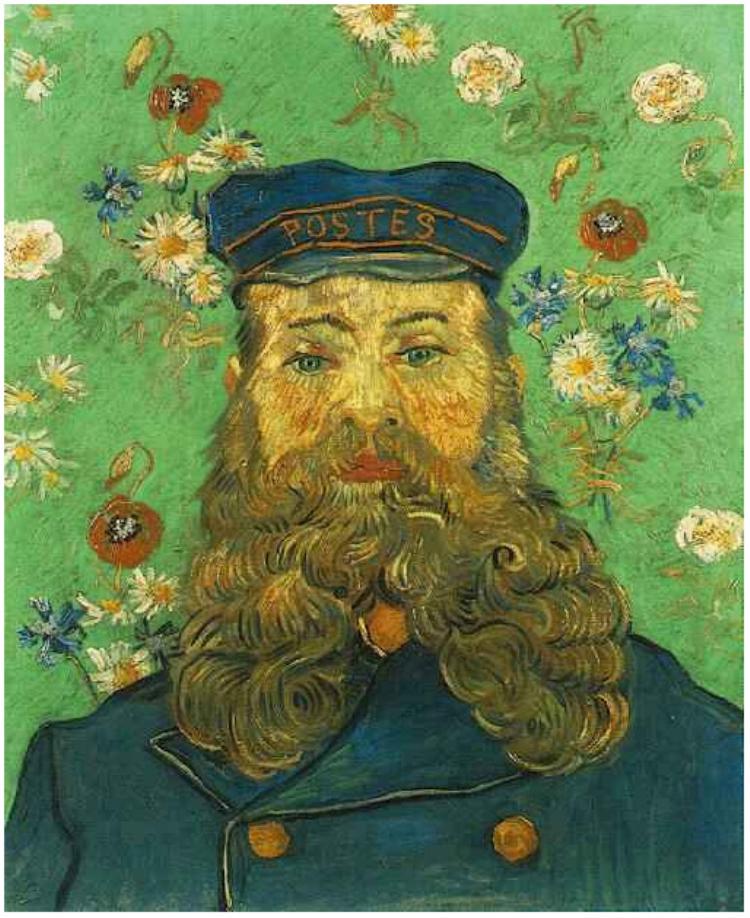

Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin (1888)

Vincent van Gogh, via Wikimedia Commons

Intuitively, I believe many would say, understandably, that repetitions are unimaginative: a writer should tell a different story with each book, or an artist should paint a different subject with each canvas. But, there’s another way to think about repetitions. I have been impressed how often repetitions – small variations on the theme – are creative. Even identical twins have small differences in their genetic makeup, appearance and behavior. Certainly no twin thinks himself redundant! Repetitions allow detailed explorations that cannot be achieved in a single shot. A scientist might say that an ideal set of repetitions is a series of experiments varying one variable at a time, or more realistically when it comes to art, limiting the abundance of variables.

Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin (1889)

Vincent van Gogh, via Wikimedia Commons

Much of the finest works come from repetitions made by the artist. Even slightly different perspectives of the same subject are valuable and creative. Claude Monet’s haystacks come to mind: a similar subject at different times of the day. Vincent van Gogh’s repetitions are among his finest paintings: the postman Joseph Roulin; the bedroom; Le Berceuse (see E. E. Rathbone, W. H. Robinson, E. Steele, and M. Steele, van Gogh Repetitions, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2013).

Repetitions – variations and experimentations on the same or very similar subject – reveal complexity and expose the numerous decisions the artist struggled with: composition, shape, color, or wording, depending on the medium. A slight tilt of the head of a sculpture can make it a different piece of art altogether. Translations of foreign books are particularly interesting, since they represent attempts to make replicas in a different language, yet the choice of idioms, verbs and adjectives can make a profound difference in meaning and tone. Repetitions are like mini-collections – siblings – buried within the collection, wonderful additions both intellectually and artistically. Similar pieces are like playing with context, each slight change emphasizes a different quality of the work, a different perspective on the same thing.

Repetitions are not lacking in imagination; only collectors who don’t recognize the value of repetitions are lacking in imagination.

Leave A Comment