Our lives are calibrated by death, the end, when we can no longer enjoy what or who we love. My father often said, “There’s nothing better than life.” I am conscious of age because I want to experience as much as I can, savor my blessings and health to the maximum, and leave my mark before I say good-bye. Ironically, the certainty of death drives our lives. I would be pleased with the epitaph, “He tried his best.” I don’t believe in an afterlife to lick my wounds and pamper my soul forever. It’s now or never for me.

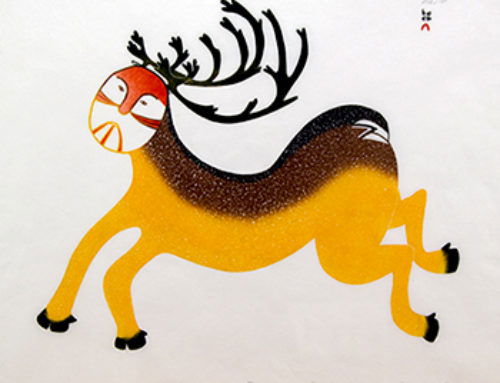

What a privilege to have such thoughts – all about myself! The story I see of Inuit death, carved in stone, is quite different.

In a previous blog I stressed the importance of the Inuit family – fathers and sons for hunting, mothers and daughters for domestic chores of cooking and sewing, along with the continuity and respect for elderly grandparents. But surviving the harsh Arctic conditions and the paucity of social safety nets put a wedge between self-absorption and requirements for survival.

I show in the slideshow below selected Inuit sculptures from my collection that portray strikingly, as only art can do, how Inuit coped with death.

In the relief sculpture by Miriam Marealik Qiyuk, a baby boy lies beside his sleeping parents in their igloo. A baby girl lies on the right of the barrier, probably representing the doorway into the igloo. This puts the baby girl outdoors, where she will freeze to death. The abstract bird’s head, a trademark of Miriam Qiyuk’s sculptures, is a helping spirit to take her soul to heaven. The reason for this tragedy, as I understand it, is that baby girls were often sacrificed to limit the number of mouths to feed, while boys were essential for hunting food to sustain life. It is also true that at times baby girls were hidden, and there are sculptures that show them covered by a blanket or article of clothing for protection. It is possible, then, to envisage the barrier in this Qiyuk sculpture a blanket over the girl, and the bird spirit guarding her safety. Such ambiguity reveals the complexity and inherent conflicts which define our lives revealed in art.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

The threat of starvation if hunting or fishing was compromised for one reason or another is shown in the shocking sculpture by Arnaqu Ashevak of a starving Inuk, a situation that sadly was not unusual.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

While death by starvation was a constant threat, hunting too threatened death. This sculpture by Isaac Alayco shows a dramatic scene of a confrontation of a polar bear and hunter: death for the hunter was certainly a possibility!

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

This sculpture by Qavaroak Tunnillie shows a dead hunter in the mouth of a bear. Remarkable about this carving is its ambiguity. At first glance it appears that the bear has virtually mangled the hunter. Yes, no doubt there’s truth in that, but the other striking feature is that the bear is carrying the body upward to heaven, to an afterlife. A seal behind the dead hunter, not seen from this view, is grabbing his foot, mirroring the respect the Inuit have for animals with respect by animals for humans.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

Shaman have powers beyond death among the Inuit. This sculpture in beautiful green serpentine stone by Abraham Anghik shows a shaman, part bear, part human, pierced through the heart by a spear, yet still alive. Such resilience, coupled with belief in the afterlife, must provide welcome relief against living under the pressure of death.

Photo by Michael Kingsberry, Select Cut Media LLC

As much as the Inuit respected and valued their elders, historically hardships led to acceptance of death that is foreign to us, except perhaps in cases of assisted suicide. The moving and simple sculpture by John Atok shows a grandfather being led to death by his son.

Senilicide or manslaughter – essentially murder – was practiced at times for infirm Inuks, generally grandparents, who could no longer contribute to the struggle for survival. They might be thrown into the frigid water, left outside to freeze, abandoned in the wilderness, or subjected to another pathway leading to death, depending on the difficulties facing the family at the time (http://www.theinitialjourney.com/features/eskimos-old-age/). We view this with horror, however belief in an afterlife no doubt softened the blow, and escape from the cruelties of old age allowed death with dignity for the benefit of the family.

Leave A Comment