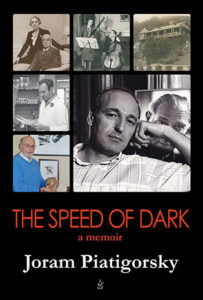

I started writing my memoir, The Speed of Dark, as a series or personal essays in the literary journal Lived Experience published in British Columbia. Over nine years it crystallized into a book released this week by Adelaide Books. With the writing behind me, I reflect on the journey that became my memoir.

After 50 years of science, I turned my attention to writing fiction and published a novel, Jellyfish Have Eyes, which was published in 2014. Although the novel incorporated some ideas from my years as a scientist and knowledge from my research on jellyfish eyes, it was fantasy constructed entirely in my mind, as were the series of short stories I had written before that. When I started to write a memoir, I entered a new world that had to be based on true experiences. It wasn’t about dreaming up a compelling story or weaving together a historical account on a selected topic; I just had to report on my life. No problem, I figured. That should be relatively easy. I had already lived the plot and knew all the characters.

After 50 years of science, I turned my attention to writing fiction and published a novel, Jellyfish Have Eyes, which was published in 2014. Although the novel incorporated some ideas from my years as a scientist and knowledge from my research on jellyfish eyes, it was fantasy constructed entirely in my mind, as were the series of short stories I had written before that. When I started to write a memoir, I entered a new world that had to be based on true experiences. It wasn’t about dreaming up a compelling story or weaving together a historical account on a selected topic; I just had to report on my life. No problem, I figured. That should be relatively easy. I had already lived the plot and knew all the characters.

As I wrote, however, my mind bounced around in a myriad of directions – childhood, adolescence, school, science, travel; how to put these disconnected times of my life together into an interesting story that someone would want to read or who would benefit by reading? Had I done anything interesting enough to attract an audience? My father’s journey from the pogroms in pre-Bolshevik Russia and rise to international stardom as a cellist, and my mother’s background as an heiress of the French Rothschild banking dynasty and diverse accomplishments in chess, tennis and sculpture made compelling stories. Why, I wondered, would anyone want to read about me, a government scientist who had lived a conventional life in the peaceful United States? I had never engaged in battle or narrowly escaped war as my parents had, or endured poverty, or suffered injustice, or triumphed by overcoming obstacles.

Then I read Marcel Proust.

It started like this: I was in a bookstore in Point Reyes, a cozy California nook an hour’s drive from San Francisco, when In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust caught my eye. I read snippets of Swann’s Way, the first volume. The extended sentences comprising strings of phrases, similes and metaphors fascinated me. I bought the book. A few months later, craving more, I read the other five volumes of his autobiographical novel. I felt a certain resonance with the scenes of elegant social gatherings and gossip among the sophisticated guests, with my childhood trips to Paris after the war to visit my maternal grandparents. Historically, my mother’s family had been a part of Proust’s aristocratic world, and he mentioned some of my relatives who attended the salons in his novel. This awakened an ephemeral sensation, a distant déjà vu, associated with my childhood and French mother, which made me an uninvited guest, a voyeur, at Proust’s salons. I even heard my mother’s insistence within this deep layer of myself that I act with unimpeachable decorum because I’m a Jew, a Dreyfusian in Proust’s society, who must remain above reproach as a shield against anti-Semitism.

Proust’s captivating novel emerged from his relatively uneventful and sickly life. He enhanced occasions where nothing of note actually happened into momentous moments. Marcel, Proust’s fictional narrator, like Proust himself, roamed museums, vacationed by the seaside, visited friends, socialized, introspected and nurtured neurotic torments born in his aristocratic French society as he dwelled on his signature issues of homosexuality and anti-Semitism. His experiences alone had minimal interest until filtered through his thoughts and feelings.

Perhaps this is not a perfect analogy, however, imagine someone refusing to relinquish a childhood doll through tempestuous adventures and dangers of war. Wouldn’t the reasons for treasuring the doll be as compelling as the specific experiences of war, or maybe even more so? Did a memoir have to rely on elaborate plots or world-changing events? Couldn’t it be compelling by peering inward while reaching outward in the life one has created in the world one has inherited?

And so, I started to write about being born in the rural Adirondack mountains as the first American citizen in my European family who escaped Hitler on the day France and England declared war on Nazi Germany. Unlike other memoirs about rising from adversity to achieve success, mine was going to be about finding my identity and establishing a distinct voice in a family where the extraordinary was ordinary.

My memoir – The Speed of Dark – is about breaking the chain of my European lineage of art, music and banking by pursuing a career in science in vision and genetics in America influenced by my background of artists. You can buy it on Amazon.com. I welcome your comments and reviews.

Leave A Comment