Editor’s note: Fusing memoir and fiction, Joram’s own research fuels the adventures of his protagonist Ricardo Stein in Jellyfish Have Eyes. As an NIH scientist acclaimed for vision research, he had 20 years of dissecting the eyes of vertebrates under his belt when he learned that, indeed, jellyfish have eyes.

Which leads me to this week’s questions: “What was it about jellyfish that caught your attention? And what was it like to dissect their eyes?”

Most of us view eyes as fascinating, complex sensory connections to the world. But there’s much more to eyes than that.

Face it: eyes are seductive. I’ve heard women talk about ‘bedroomy’ eyes, and I admit to have been entrapped by alluring eyes of inviting women. And who doesn’t submit to the pleading eyes of a puppy begging for a cookie? Eyes can be passageways into the heart as well as reflectors of thoughts and feelings of their owners. Most of us view eyes due to our experience as fascinating, complex sensory connections to the world. But there’s much more to eyes than that. Spiders and squid and scallops and snails and flies and crabs – the list is extensive – also have eyes, some that look surprisingly like ours, and some that look completely different, like the compound eyes of insects for example. That many invertebrates have eyes is common knowledge among many laymen and virtually all biologists.

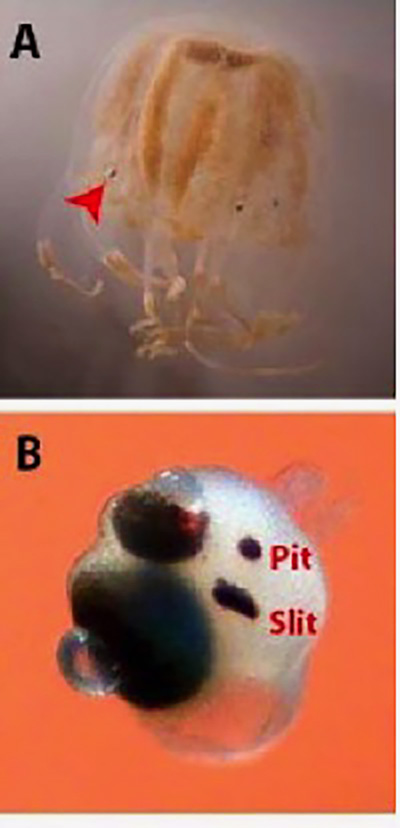

But imagine my amazement when I first saw a photomicrograph of a jellyfish eye when browsing through a book on invertebrate vision. I was flabbergasted. Jellyfish have eyes! Who knew? Certainly not me. No one I asked knew that jellyfish have eyes, neither the Scientific Director of the National Eye Institute (where I worked), nor any of the vision research scientists I queried. No one! And yet the book said that it’s been known from at least the 1870s that jellyfish have eyes, some complex with resemblances to the image-forming eyes of vertebrates, and some that detect light but do not form an image. The sophisticated jellyfish eye, called an ocellus, the image-forming eye, has a cornea, lens and retina with vertebrate-like photoreceptors including black pigment to prevent scatter. And jellyfish predated humans by some 7-800 million years on planet Earth. I guess we humans didn’t invent everything.

I was seduced and intellectually challenged by the jellyfish eye. What do jellyfish see, and why do they need to see anyway? Questions flashed through my mind. In addition, that so few knew that jellyfish have eyes boosted my interest and curiosity. I love to cast light on dark shadows, go where others have not gone, open doors rather than try to rush through doors that have been opened by others. For me, research means probing the unknown, and jellyfish eyes certainly fit that category. Anything discovered is new; the possibilities are limited only by the imagination. I was Ricardo Sztein, the protagonist in my novel Jellyfish Have Eyes, before he was even born. Like Ricardo, I “saw jellyfish as a poem and their eyes as a laboratory.”

I told my close friend Joe Horwitz (a modified Benjamin in Jellyfish Have Eyes), a professor at the Jules Stein Institute at UCLA Medical School, that jellyfish have eyes and he got excited too. We decided to team up and explore these little-known eyes. But how should we go about this in landlocked Bethesda? I wrote to two scientists I traced down that had published much earlier on jellyfish eyes – one in Australia and the other in Puerto Rico. Charles Cutress from the Marine Station in La Parguera, Puerto Rico responded, and Joe and I traveled there to learn how to find jellyfish in the mangrove swamp and obtain their eyes. We had no idea if we would be successful. The only clear scientific question I had at the moment was to identify the main proteins (the crystallins, my specialty) in the jellyfish lens. Cutress was our benevolent teacher, and then he morphed into the partly fictional Harold Feeman in my novel many years later.

What a great adventure! I loved it. I’d become a pioneer trying to forge a new path: Piatigorsky and Horwitz were Lewis and Clark. Cutress taught us how to locate the jellyfish in the mangrove swamp, which was so beautiful. He tried to remove the eyes from the inside of the jellyfish, which he had never done before, but I soon discovered it was much easier to simply grab the eyes with jeweler’s forceps from the front, since the eyes were embedded in a fascinating balancing structure called a rhopalium that dangled from a stalk in a cavity in the bell open to the sea water. I was able to get virtually thousands of rhopalia for study. Since I’d had a lot of experience in micro-dissection through a microscope, I was eventually able to excise the transparent lens (approximately 5/100 thousandth of an inch, barely visible without the microscope) from the eye with finely sharpened jeweler’s forceps. I sat hour after hour doing this very fine dissection. I was in a cloud of private contemplation where dreams are free to roam.

Well, Ms. Editor, does that answer your question about how I got sucked into jellyfish? There’s so much more to say, but enough for now. The take-home messages for me are: do what you love, if you are lucky enough to have the opportunity, and don’t be confined to what you already know, which is inevitably limited. There’s a bountiful, beautiful and mysterious world to explore, and always will be.

Great post, very interesting

Thanks! Stay tuned for more.