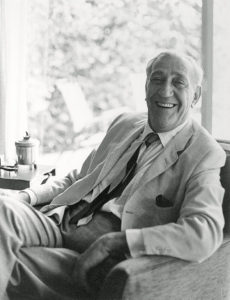

Mr. Blok, which was written by my father, cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, was published posthumously by Adelaide Books. Excerpts from my introduction in the book are below.

Hidden Artistic Treasures

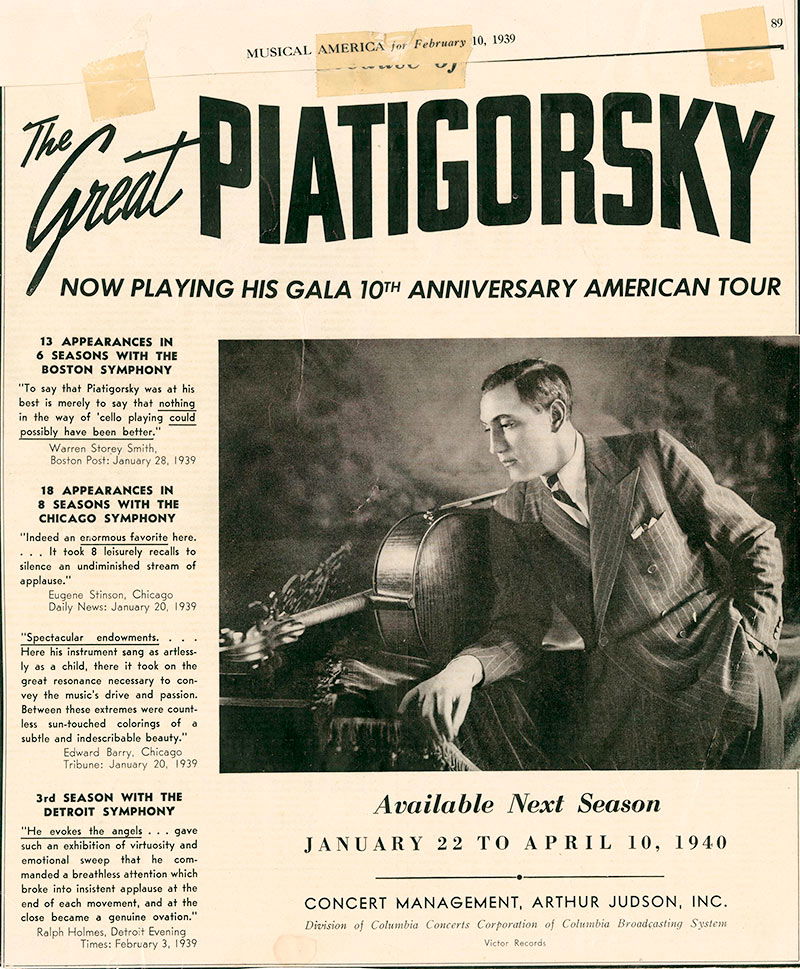

Announcement of Gregor Piatigorsky’s 1940 American Tour. Click to enlarge.

Time passed and Papa died from lung cancer in 1976; he was 73. The manuscript languished in my mother’s house for 50 more years. When she died at 100 in 2012, I found several copies of the typed manuscript, which I gathered along with Papa’s other writings, including short stories, essays, poems, limericks and even the beginning of a second volume of his autobiography, Cellist. He often wrote on scraps of hotel stationery on his numerous travels concertizing.

Papa was well-known for being a spellbinding raconteur, often exaggerating and twisting reality into new shapes and sizes, and this talent jumps out of everything he wrote. Mr. Blok has many examples of tangential episodes and scenes that are typical of Papa’s storytelling. The story radiates in various directions echoing Papa as he spoke in overlapping circles of free associations. These digressions enrich the novel greatly.

Evolving Storylines

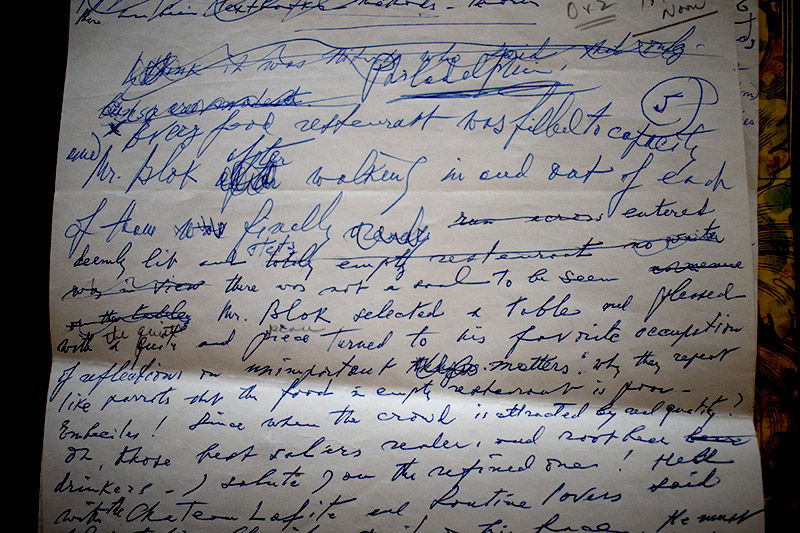

Papa’s handwritten notes about Mr. Blok. Click to enlarge.

Mr. Blok was written in English and the present version has not been altered. I am unaware that Papa ever had a professional editor. He read his novel as it progressed to Adele Friedman (today Adele Siegal), who typed the manuscript from her shorthand notes. I asked Adele, now in her nineties, about her experience typing Mr. Blok. She said that she first met with Papa to type the beginning of Mr. Blok in Philadelphia shortly before we moved to Los Angeles in 1949. Papa would have been 46. She told me that Papa dictated from his notes, and between his accent, the weird story and her awe at being in the presence of the famous musician she was “totally flummoxed.” She typed the manuscript from her shorthand notes and continued to meet with Papa to type the novel as it progressed in the 1950s. Adele has remained a treasured friend of our family.

I recognize Blok as a tormented fantasy of Papa, an original anti-hero bursting with ambition, flipping back and forth between exuberant inspiration and waves of sadness verging on despair. My friend Barbara Esstman, an author and editor, said that Mr. Blok sounded like “the French Symbolists poets got together to write a novel. Or maybe Kafka and Gogol went drinking together…very dreamlike and surreal… so well-written and the intelligence and artistic sensibility of the author…so astronomical.”

Predicting Future Surprises

Papa was fascinated by nature, real and imagined. Click to enlarge.

Blok’s runaway imagination, mixed with humor and absurdity, pervades the novel and is sometimes prophetic for its era. Unwittingly, he predicts pollution of Earth when he says, “Our stomachs have shrunk, and yet our excrement has increased, polluting all our rivers and lakes, rendering the life of fish impossible and our water undrinkable.” I read recently that a quarter of the planet is experiencing severe water shortages.

Blok also anticipates modern conveniences, some consistent with computers: he speaks of self-driving cars that have television screens behind the driver’s seat, protections against collisions and can recognize red and green lights. His fancy new car has innovations even beyond what presently exist.

Artistic Connections Transcend Time

Mr. Blok by Ismael Carrillo for Notes Going Underground by Joram Piatigorsky.

Finally, I felt an eerie connection with Papa filtered through Blok, especially at the end of the novel, when I recalled reading The First Man by Albert Camus. The autobiographical novel, found in the wrecked car in which Camus was killed, was published posthumously 34 years later. The story is about Jacques Comery’s, Camus’ alter-ego, childhood in Algeria, with an underlying theme of searching for his father. In a telling passage, Jacque, 40, stands by the grave of his father, who died at 29, he feels the crumbling of the internal statue he erected of his own identity, realizing that he is the continuation of his father’s life. In my case, I was struck by the similarity of the surreal characters that exist in my recent short story collection, Notes Going Underground, and Blok. Although I had never read Mr. Blok, written by Papa when I was a boy, I created independently literary characters years later that exist, absurdly and surreally, in a transition between being partially alive and partially dead – in a dreamworld, as it were – as if a porous barrier separates the two states resulting in an overlapping period between life and death. Were Blok’s surreal, often absurd adventures real or a dream? Blok asks the same question when the novel opens with him in a ditch:

“Mr. Blok thought it was a dream; but he must have been wrong. He walked through the Square one night and arriving at 20th Street, fell into a ditch they were digging for sewer pipes or something.”

How strange, and comforting, to find my mind gravitating to a similar hideout with Papa’s.

The Open Door to New Perspectives

Whether Blok is dead or alive, or awake or dreaming, I believe that you, like me, will – as Papa writes in the Forward – “find Mr. Blok a likable fellow, who will not mind in the slightest being put aside, should he not succeed in holding your attention.”

Whether Blok is dead or alive, or awake or dreaming, I believe that you, like me, will – as Papa writes in the Forward – “find Mr. Blok a likable fellow, who will not mind in the slightest being put aside, should he not succeed in holding your attention.”

Preview: Look Inside

Video Introduction

Mr. Blok was originally intended to launch at the annual Piatigorsky International Cello Festival at USC Thornton School of Music.

My video introduction, which would have played at the book launch, is below. Like many other events, the festival was canceled due to the Coronavirus.

Leave A Comment