Near the end of my upcoming memoir on my life in science, I think back on my trip to Lilloet in Canada to visit Van, my high school friend, whom I hadn’t seen in some 60 years. Van lived an independent life, including many years in a commune off the grid in British Columbia. Despite that we were kids in the same school in Los Angeles years ago, his life couldn’t have evolved more differently than mine as an American scientist with a European family, who escaped Hitler by a sliver of luck and insight, and a heritage seeped in art.

In my memoir when visiting Van, I reflected on selected episodes of my past, as if the events and thoughts and feelings I had at the time comprised a continuum of the same me – a “self,” as it were:

As we talked I was struck about how we imagined our lives as single stories, but there seemed little truth in that. We changed uniforms constantly, in our minds if not in fact, sometimes from year to year, sometimes day to day. I thought of all the uniforms I’d worn: research scientist, author, art collector, friend, husband, father, grandfather and human being, trying to resolve the layers comprising my life. Seeing Van again made clear that memories were more than footprints embedded in the past.

Memories were more like movies with evolving plots than photographs; they were modified in different contexts, and seen through different lenses under changing circumstances…I no longer saw my past confined to scientist confronting nature’s secrets, but as a time that prepared me to cross borders and explore new pastures. And then the unexpected miracle: the memories transformed into the raw material for the narratives I was yet to write.

Life may be a series of linked episodes , but it’s more interesting than that.

William Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Yes, we are molded by our history, which may be interpreted in various ways, but can’t be changed. James Gleick’s remarkable book, Time Travel, a barrel full of nuggets of mind-bending ideas, discusses the blight of the Time Traveler – the memoir author who revisits the past as if yesterday comprised sites to see again, as the mathematician Pierre Simon, Marquis de Laplace thought in 1845.

The past may be fixed and, as Faulkner said, always present, but Gleick reviews the extensive literature that our past cannot be recreated, even immediately after it occurs. Each instance stands alone.

Could this still be me?

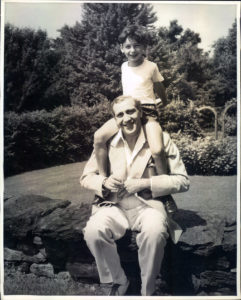

Childhood photos circa 1944-1947

In the passage above, I spoke of memories as movies rather than photographs, meaning that we sculpt the past to fit the present. But if our different experiences at different times in our lives are like a movie with a plot that advances with aging, the actors change with the episodes.

Gleick tells us in Time Travel about a man named Bob traveling back in time in Robert Heinlein’s story, By His Bootstraps. The person Bob encountered in his past times is not the same one as his later version.

Heinlein wrote, “His memory had not prepared him for who the third party would turn out to be.” (The three parties are Bob1, the young guy, Bob2, the Time Traveler, and the author, a different person altogether.)

Bob1 was drunk, and so Bob2 said, “Don’t refer to that guy as if he were me. This is me, standing here.” Bob1 replied, “Have it your own way. That is the man you were. You remember the things that are about to happen to him, don’t you?”

The time traveler in my memoir – me – cannot assume that the many versions of me encountered in my memory are always one and the same person.

Life may be a series of linked episodes, but it’s more interesting than that.

Back to Gleick and an excerpt of The Man Who Folded Himself by David Gerold, the author of Star Trek:

“A mysterious “Uncle Jim” urges him (college student named Daniel) to keep a diary, and a good thing, too, because life quickly gets complicated. We soon struggle to keep track as the cast of characters expands accordion like to include Don, Diane, Danny, Donna, ultra-Don, and Aunt Jane – all of whom are (as if you didn’t know) the same person, on a looping temporal roller coaster.”

We are several people in different uniforms, and we try to wrap ourselves into one. But we are not one person. A recreated life – a memoir – envelops truth in fiction, and pierces concrete facts with abstractions.

Wearing different costumes challenges our identity.

To further illustrate my point, I offer an excerpt from a short story I wrote a while ago and have earmarked for publication in a future collection.

Benjamin, an atheist born a Jew, sits in synagogue on Rosh Hashanah with his religious wife, pondering himself:

“…other nagging questions rattled around in Benjamin’s mind and confused him. Am I participating in earnest? I’m here, aren’t I? I’m always here on Rosh Hashanah. I’m a Jew with a Jewish wife celebrating the New Year with other Jews. Don’t people need family? Don’t I? Am I not a product of history as everyone else here? He responded to the songs, rose to the call, read, on cue, that God is one, all-powerful, benevolent, never to be doubted, always to be honored. Did it really matter that he did not believe the voice of certainty in the prayer book, or that his hand was not among those seeking the Torah, or that his lips were not brushing against the object made holy by contact with the Torah, or that he was an Atheist, with a capital A? He was there, willingly, wearing his tallit and yarmulke. Doesn’t the uniform define the person? Wouldn’t a person camouflaged in a white sheet and sporting a pointed hat listening to the Grand Wizard be branded a member of the Ku Klux Klan whatever his beliefs? Do thoughts trump actions? Isn’t the messy informal appearance of a research scientist, like himself, a part of who that person is? He was there all right. If a modern day Gestapo invaded the temple at that very moment he would be incarcerated with the others.”

Being authentic in my memoir demanded that I try to meet myself at different times under different circumstances to express the several people within me. In another blog I will touch upon how my different selves interacted with one another to knit them together.

We are several people in different uniforms, and we try to wrap ourselves into one. But we are not one person. A recreated life – a memoir – envelops truth in fiction, and pierces concrete facts with abstractions.

Born in August, 1945, and a lifelong devotee of the piano, it is my great sorrow that it was only a few years ago that I became aware of your father. Since then, I have passionately listened to his work on youtube and read everything I find about him. Most importantly, I learn from him through his spoken thoughts on life and learning. I have young friends who attend or graduated from Curtis and every time I walk into the foyer of that great institution, I feel his presence. In fact, a copy of his caricature that hangs in the hallway there hangs on the wall of my living room behind the piano of my childhood! I have also been reading about your lovely mother. What a famiky you are! My very best regards,

Famiky… I often press send too soon!????