Photo by Dmitry Ratushny, Unsplash.com

Over the past month I’ve celebrated the April launch of my short stories, The Open Door and Other Tales of Love and Yearning, by engaging in four literary conversations with fellow authors members of our vibrant literary community.

At the Kensington Park Library, my memoir workshop produced an open discussion on personal writing. Together in a room filled with aspiring and practicing writers, I touched on the art of commission and omission – what events to include and what to leave out. Then, during three separate public literary conversations with noted authors Barbara Esstman at The Writer’s Center and Sandra Beasley at The Arts Club of Washington, as well as Steve Piacente at the Day of the Book in Kensington, I was steered to consider this topic further, when they asked: What did I find different between writing science and writing fiction?

Surprisingly, while I penned strictly science for 50 years, writing fiction didn’t feel like starting from scratch. I found they both share the need for an internally consistent, advancing narrative.

Writing science requires linking facts and observations in an appropriate narrative, aimed at advancing current knowledge or an evolving story. Although science is not fiction, one still must weave data and observations into a logical narrative, as required in fiction to create characters that interact and earn credibility in a coherent story or in a memoir to recreate memories and events into a continuous story.

One of my biggest challenges in writing fiction was to learn the art of omission – what not to say explicitly in order to allow the reader to “enter” the narrative and become emotionally involved. In terms of the writer’s well-known jargon, “show, don’t tell.” Science writing, on the contrary, just tells and keeps the reader outside the narrative.

Ironically, another challenge that I found for writing fiction that differs from writing science is to include enough details of the setting and thoughts about the past, present and future – reflections and “what ifs…,” as it were. In general, we think in terms of happenings and consequences. But what happens in fiction, as in life, depends on various choices along the way. These choices are the stepping stones of fictional characters, as they are in our own lives, and are not considered in writing science. For fiction, including choices provides an important dimension.

What we didn’t major in in college, the job offer we didn’t take, the romance we didn’t pursue, the habit we didn’t form – they often belong in and enhance fiction. Are they not, in essence, the foundation of what was done and responsible for the outcome?

Thus, I found it particularly challenging for writing fiction (and memoir to a lesser extent) to decide how much to leave out to let the reader complement the story, while at the same time deciding how much reflection and details to include to transport the reader into the minds of the characters and the setting.

As I reflected on the question of omission in writing, I began thinking what part it might play in our lives.

Omission can be practical. For example, after back surgery I tried various methods to relieve pain that occurred for most movements, even the process of sitting or standing up. The Alexander technique turned out to be helpful. In contrast to strengthening exercises, the Alexander technique concentrated on not using muscles and motions that were not directly relevant for the process. Don’t flex your shoulders if you want to stand up; it won’t help to use muscles not connected to the process of standing up. What a difference it made! Omitting unnecessary movements was very important to relieve pain.

Athletes who have mastered their activity – whether tennis, skiing or hiking – never seems to be exerting themselves. Why not? Because they have learned to not use muscles or perform movements that are not directly required to accomplish the task.

The power of omission has widespread application. When concentrating on any task, the ability to omit interfering thoughts, feelings, or actions not related to the job at hand saves energy and directs focus. Knowing what to omit – perhaps a negative way of thought to some extent – can be as important as knowing what to include as a pathway to success.

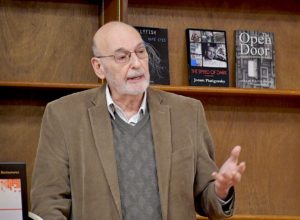

Joram speaks at the Kensington Library’s “All the Write Stuff–A Workshop for Writers”

Thus, it is not only writing in which omission has a key role; it’s in life.

What we didn’t major in in college, the job offer we didn’t take, the romance we didn’t pursue, the habit we didn’t form – they often belong in and enhance fiction. Are they not, in essence, the foundation of what was done and responsible for the outcome?

Leave A Comment