Thank you, thank you for all the happy birthday wishes I received this week on Facebook and elsewhere. As I commented in my Facebook response, having all of you as my friends is the best present I could have.

When I was young, birthdays were exciting, special, my day, a day for presents and cake. Then came middle age, maturity (we hope), a day to relish the moment and plan for the next. And now, older age (note, I still hesitate to say ‘old age’), a time to appreciate and look back, to assess, but not yet (at least, hopefully, not for me) to wave the white flag or deny a future. I think of my mother’s words: “If you’re not growing, you’re dying. There’s no status quo.”

I’m writing and still striving.

But we all die sometime and must accept that as well. After a lengthy battle with congestive heart failure, my brother-in-law Larry, Lona’s brother, died a few weeks ago. He was 77, my age, when I just celebrated my birthday. As I appreciate my life, I also look back on his and am reminded how complex and worthy people are – as he was – as we all are – and how grateful I am to have been given the gift of life.

Larry Shepley (1939-2016)

Lawrence Charles Shepley (1939–2016)

Larry, my wife Lona’s only sibling, guided his death like a deft captain pilots his ship to the dock. Already in February, 2014, and updated in April, 2016, before he passed away of congestive heart failure on December 30, 2016, Larry wrote a document – If I Die – in which he listed his assets, social security number, insurance policies, various contracts with builders, computer passwords, car, maid, friends, colleagues, the Gilbert and Sullivan Society – his life.

He wrote, “Please be assured that I don’t fear death. I enjoyed life, and I would have enjoyed continuing to live, but everyone must die sometime.” He didn’t want solicitations in his memory or any memorial service for him. He suggested two possible, versions of his obituary, both short and modest; one was in the third person, the other in the first person, which he ended simply, “Farewell and good luck.”

No fuss, no attention focused on him.

Nanette (Nan) Detlaff, his devoted friend for some fifty years, remained lovingly in his room day and night the last few weeks in the nursing home in Austin caring for him, supporting him, being there. Many other long-time friends stood by as Larry weakened in the last two months of his life. Larry’s friends, his lifeblood, loved him.

Larry had been plagued with heart trouble for many years. An implanted defibrillator rescued him numerous times after he lost consciousness. When all hope was gone, he asked his hospice doctor to turn off the defibrillator, and a few days later Larry closed his eyes and died. He accepted death with uncanny calm and reason. I’ve never seen anything like it. He said he was curious what death would be like. Curious. He always wanted to learn something new, even about death.

Everyone who knew Larry had rightfully the highest regard for him. His high school friends noted his intelligence and predicted great success in his future scientific career in their comments on the class photograph. Some referred to him as a genius. His family had a similarly high regard for him: he had a remarkable memory, a great gift in mathematics and a serious, intellectual demeanor. He won honors in science fairs and excelled in school. After receiving a B.A. from Swarthmore College in 1961, he earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in physics from Princeton University in 1965. John Wheeler, a legend in the field of cosmology, was his mentor. Following graduate school, he did two years of postdoctoral studies at the University of California at Berkeley under the tutelage of Abraham Taub, another important figure in mathematics and general relativity.

Larry became an Assistant Professor of physics at the University of Texas at Austin in 1967 and was promoted to Associate Professor in 1970. His former mentor, Wheeler, also joined the physics department at the University of Texas, which had become world-renowned in relativity and cosmology, and remained Larry’s friend and colleague. Larry published some thirty articles in professional journals and co-authored Homogeneous Relativistic Cosmologies (Princeton University Press, 1975) with Michael Ryan, and Classical Mechanics (Prentice Hall, 1991) with Richard Matzner. Larry loved to teach and mentor students. He was active in the physics department as Associate Director of the Center for Relativity, Vice Chair for Graduate Affairs and Graduate Adviser, and Departmental Minority Liaison Officer.

I had opportunities to speak at length with Larry when he visited us in Bethesda. We were on the same liberal wavelength in politics and love of science, however he never spoke of his own research. When I asked him about his goals in physics – his professional ambitions – he said that he loved learning about what was going on and newly discovered by others. That was it; he seldom, if ever, mentioned himself, his ideas or how his work figured in physics. He never expressed excitement or disappointment about his career. If pressed, he avoided discussion by saying he followed many incorrect leads on understanding the universe. I am not a physicist, but am confident that his modesty short-changed many strides forward in his studies on general relativity, relativistic cosmology and the foundations of classical mechanics.

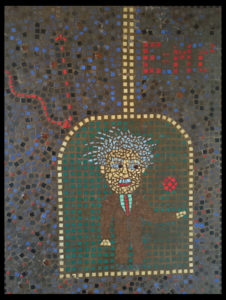

Larry was a consummate, dispassionate, pure physicist. He saw physics as larger than any one person, including himself. Einstein was an exception, as judged from the many pictures and beautiful mosaic Larry made of him that hung in his bachelor apartment.

Thus, I knew Larry at a distance, as it were. He lived in Texas, I in Maryland. We had relatively few get-togethers due to our busy lives. My knowledge of him as a physicist was limited to his brief answers to my naïve questions. Recently, a colleague of his told me that his physics was rock solid, but added that he didn’t follow fashionable paths as they arose, and this resulted unfortunately in his receiving fewer recognitions than he deserved.

Larry was exceptionally intelligent, had a love for debating contentious issues, and benignly eccentric, with the orange socks he wore on all occasions, whether informal or formal. They were his sign of individuality, his trademark.

He retired in 1995, only 56 years old and in prime health – extremely young from my viewpoint – however he kept contact with colleagues in physics, attended lectures at the University of Texas, and went to conferences as an emeritus professor. It was his way of remaining involved, yet on the outside, without being harried, charting his own path, being simultaneously involved and independent.

Although I had known Larry for close to fifty years, I felt he kept an important part of himself behind a protective veneer. Going to Austin with Lona to clear out his apartment and prepare it for sale gave me an opportunity to get a deeper understanding of the complex person he was. We spent six intensive days meeting his friends and associates, going through his extensive files, and donating his clothes, books, furniture and other items to his friends and charities.

I knew that Larry was an accomplished mathematician, but was uncertain how his mathematics related to his physics. In a document labeled simply “Princeton,” which he wrote commencing graduate school, Larry stated, “I am not especially interested…in refining existing mathematical statements of physical facts (which is often meant by ‘mathematical physics’) but rather in exploring new mathematical descriptions of new or existing phenomena (which is often meant by ‘theoretical physics’). Mathematics itself…interests me…from the point of view of an avocation.”

Although he wrote of mathematics as an avocation, he went on to question that by considering his desire to couple mathematics with physics:

Larry’s Einstein mosaic

“The question has often arisen with me as to whether I should call myself a physicist or a mathematician. I am very much interested in the description of phenomena from a simple axiomatic point of view, and in this sense I am a mathematician. However, since physics is especially suited to simple formulations of this type and has, moreover, a tradition of this kind of treatment, I call myself a physicist. Indeed, as an adequate job within the field in which I hope to work requires a thorough knowledge of experimental facts, I must do a great deal of work concerned with what is known and the experimental basis of knowledge as good as mathematician as possible so that I may have facility in regarding a problem with an eye to the various ways a fruitful description may be formulated. It goes without saying that a facility in dealing with this formulation is necessary also: that is, a facility with the techniques of mathematical analysis of situations.

“For these reasons I hope to do in graduate school what I have done in undergraduate school: work as a physics major with a minor in mathematics fully as strong as my physics major.”

I don’t know whether Larry wrote this for Princeton or for himself, but in either case, it portrays his deep involvement and ambition in physics from an early age.

Larry kept files and files and files of details in his apartment. He threw little away.

Larry loved to travel. He went almost exclusively on guided tours and interacted socially with his fellow tourists. As with his physics, in which he preferred to explore the new rather than refine the old, Larry traveled to new places rather than going repeatedly to the same places. Among his travels, he visited: Japan (1990), Dominican Republic and Chile (1991?), Alaska (1993), Spain (1994), Belize (1998), Turkey (1999; with parents, Lona and me to view eclipse), England (2000), Antarctica and Falkland Islands (2001), Norway (2001; for my son Auran’s wedding), Zimbabwe (to view eclipse) and Southern Africa (2001), Toronto (2003), Panama and Costa Rica (2003), Florence (2004), Danube River (2005), Russia and Finland (2006), Chesapeake (2008), Scotland (2008), Channel Islands (2009), China (2009), Athens (2011), Morocco (2011), Portland (2011), Australia (2012), New Zealand (2012), Mississippi (2014), Cambodia (2014), Cape Cod (2014), India (2015), and Ireland (2016). No doubt I missed a few. For each tour he kept an extensive hand-written daily log describing the weather, the food, the sites, the people, the traveling. It seems likely that the increasing number of trips he took in the last five years of his life was an effort to see as much of the world as he could before his heart gave out. He struggled to finish his trip to Ireland – his last – due to heart troubles; he knew then that his tourism days were over.

Haunted by the threat of death was not new to Larry. He struggled with asthma as a child, so illness was a lifelong problem for him. I was especially surprised to run across another If I Die document he wrote when he was 38 years old that was similar in style to the one he wrote at the end. Imagine, he orchestrated his death on paper at 38, an age when most of us have enthusiastic plans for the future and feel immortal. It appears that Larry’s veneer hid a vulnerability wrapped in the burden of death for a long time.

I was puzzled why Larry retired in 1995 when only 56 years old. He was healthy, active, loved physics and was on the faculty at one of the best academic centers for his field. I’m not capable to judge his career as a physicist, but I was surprised that his expertise and contributions to the University of Texas for 28 years, 30 physics publications in professional journals, two well-received textbooks, two edited physics books (Cosmology: Selected Reprints; edited with A.A. Strassenburg, American Association of Physics Teachers, 1979; and Spacetime and Geometry – The Alfred Schild Lectures (edited with R. A. Matzner, University of Texas Press, 1982) and extensive teaching involvement (mentored 13 Ph.D. graduates) wasn’t sufficient to keep him eager to remain on the forefront of physics.

Larry clearly didn’t want to quit physics when he retired. He stayed on at the University as an emeritus faculty member and said that this allowed him to continue doing what he wanted to in physics – go to lectures, speak with students and help out when needed, attend conferences without obligations. In short, being an emeritus physicist in good health and active allowed him to live a freer scientific life. While he did exactly that, there was another, more tormented side to Larry that remained partially hidden behind his veneer, which, I presume, played a significant role in his early retirement. Larry’s files revealed numerous frustrations concerning politics and the University administration. Although I had an inkling of this, I didn’t appreciate the extent of his torment until I went through his files after he died.

Larry was often troubled by what he considered unacceptable shortcomings in the administrative system at the university, and this led him to resign from a number of committees.

Already in 1972, he resigned as Vice-Chairman for Graduate Affairs and Graduate Advisor, although he was always devoted to students. In his letter of resignation, Larry writes, “I have found that my abilities and temperament are completely unsuited for these jobs and that I have become increasingly irascible and bad-tempered. My research and teaching have suffered immensely, and I am unable to devote the time I would like to those projects of departmental interest I have formerly enjoyed.” Exasperated by a struggle to increase his salary, Larry wrote to the Physics Advisory Committee of his “increasingly purple complexion” and that he was “holding his breath until the university administration changes for the better but that is another Quixotic fight.” After appointment to the Equal Opportunities Committee of the College of Natural Sciences in the early 90s, Larry wrote to the Dean that “it would serve no useful purpose to go into details about why I am resigning, in spite of the fact that I strongly feel that my way of thinking and yours are incompatible. I have therefore decided upon a simple statement, unless requested otherwise…I herewith resign as chair and as member of the Equal Opportunities Committee…” Larry also resigned as Minority Liaison Officer of Physics in 1994. Larry was adamant about his ideals and wrote numerous other letters of protest, such as against the Proposed New Smoking Policy at the University of Texas and against ROTC.

Larry’s quiet demeanor hid the turmoil within.

Enough said. I believe I would have agreed with Larry’s objections, but the important point is that his resignations were to be able to devote his energy to the ideals of physics and teaching, and were not for professional self-advancement. He did not want to be diverted by politics and administration, and I believe that this contributed greatly to his early retirement and less career recognition than he no doubt deserved.

Larry was very active in his retirement years. In addition to traveling, he had many interests. One was food and cooking. He had more exotic spices and cans of interesting foods than I have ever seen in a home. That explains why his travel logs listed the menus of his meals, even those he had on airplanes, stating which courses he liked and which he didn’t. He collected wines and had wine tasting events with colleagues. He loved to entertain, which he did frequently for students, faculty and friends, and found innumerable excuses for a party. He made mosaics – a beautiful one of Einstein mentioned above – and various artistic works of colored glass bounded by metal. He was especially proud of the glass/metal sculptures of the seven deadly sins he made and displayed on the wall of his apartment. Interesting photographs, paintings (some by Lona) and bronzes (made by his grandfather), masks, ethnic rugs, his computer and television, files, his bed, dining room table (made of cherry wood by his father) and kitchen comingled with books on physics, history, fiction, art and cooking; all fused seamlessly in one large space that he designed. He even liked to knit, mainly simple squares. He said, “It takes my mind off snacking while watching television.” Larry loved music and played the flute since childhood. He had a strong connection with the Gilbert and Sullivan Society in Austin after retirement and served as its president for a year (2000-2001).

Larry was very active in his retirement years. In addition to traveling, he had many interests. One was food and cooking. He had more exotic spices and cans of interesting foods than I have ever seen in a home. That explains why his travel logs listed the menus of his meals, even those he had on airplanes, stating which courses he liked and which he didn’t. He collected wines and had wine tasting events with colleagues. He loved to entertain, which he did frequently for students, faculty and friends, and found innumerable excuses for a party. He made mosaics – a beautiful one of Einstein mentioned above – and various artistic works of colored glass bounded by metal. He was especially proud of the glass/metal sculptures of the seven deadly sins he made and displayed on the wall of his apartment. Interesting photographs, paintings (some by Lona) and bronzes (made by his grandfather), masks, ethnic rugs, his computer and television, files, his bed, dining room table (made of cherry wood by his father) and kitchen comingled with books on physics, history, fiction, art and cooking; all fused seamlessly in one large space that he designed. He even liked to knit, mainly simple squares. He said, “It takes my mind off snacking while watching television.” Larry loved music and played the flute since childhood. He had a strong connection with the Gilbert and Sullivan Society in Austin after retirement and served as its president for a year (2000-2001).

Larry’s loyal friends and students always figured in his thoughts and activities. He was a mensch with much to offer.

Perhaps least known about Larry was his love for his golden retriever, Gilbert, pronounced “Jillbear,” who was a puppy from the litter of our golden retriever. The full name Larry gave his puppy was Gilbert’s (Jillbear’s) Disease, in honor of a slight case of hepatitis, thought to be Gilbert’s Disease, which Larry (may have) contracted just before he obtained the dog. I asked Larry several times after Gilbert died whether he was going to get another dog, but he said matter-of-factly, “No.” He didn’t want another dog. I took that at face value: he was busy and did not have time to give to another dog. Fair enough.

But when I opened Larry’s thick file on Gilbert I discovered a remarkable, hand-written moving eulogy that Larry wrote after he returned from a three-week trip to Hawaii in July, 1983, and learned that his beloved golden retriever had died in the Canine Hilton (the kennel) the previous week. Quotes extracted from Larry’s eulogy revealed his deep love for Gilbert, who was clearly irreplaceable for him.

“He was a fine, even-tempered person, even with children… He was a wonderful dog. I loved him…I will always cherish him…I dedicated Homogeneous Relativistic Cosmologies to ‘G.D.’, i.e. Gilbert’s Disease…I miss his smell at night more than the noise he made…I had Gilbert’s right ear tattooed with the first 5 digits on my social security number 57852……He had a beautiful smile…I remember well the first and last time I ever saw him – I cried…I worried what I’d do if a sudden nuclear blast occurred or a nuclear war – how to protect Gilbert… I haven’t prayed yet to God – but if there is a God, here goes – Please, God, protect and help Gilbert. Thank you…Gilbert, I love you and miss you…Rest in peace. Good Dog.”

Larry lives on in me, as he does in Lona and the rest of his friends who loved him.

Joram,

This is one of the most beautiful things I have ever read. I did not know of Larry’s death, and I never met him, but I feel like I knew him after reading this. Of course, I had heard his name, and knew of his existence, but never had the pleasure of meeting him. Thank you for filling me in on his amazing life, and life force.

Please send Lona my condolences. Having lost all of my brothers, I know what a void is left in her life, and I am glad she has you to help fill it.

Again, think you for giving me the opportunity to “meet” Larry.