Creativity is often judged by novel productions of one sort or another, such as science discoveries that lead to new paradigms; art creations, such as paintings, sculptures or prints; literature, including innovative novels, poems or essays; music compositions; even original thoughts, or for that matter, old thoughts considered in new perspectives.

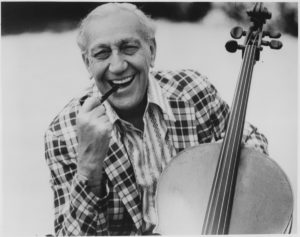

My father Gregor Piatigorsky, the great cellist, believed that a composition can never be played exactly the same.

Performance art – transient creativity – is free as the wind and remains as inspiration and influence. There is nothing concrete about transient creativity. It’s a momentary thing. Examples include acting, laughing or crying at will, that creates a new person conceived by the writer and director; an actor can make a dour audience happy or an indifferent audience sad or despondent. A concert is another form of transient art; a musician can make an instrument sing like an angel and transform notes composed by another to feelings that affect the audience.

When I played tournament tennis as a teenager, I was always able to identify a player in a far-off court by their strokes and movement.

Is the performance artist only a messenger, not the message? Is the actor or musician creative?

I remember asking my cellist father what he thought about creativity when he played the same pieces repeatedly. Did he get bored?

“No matter how many times I play a composition, it’s never exactly the same,” he said. “I would be surprised if the composer thought it was exactly the piece he wrote.”

“But is it creative, since someone else composed the music?” I insisted.

“True, yet the performer re-creates, and with each re-creation, the same composition sounds a little different, and it’s always personal. The music is mine if I’m the performer, and then the audience’s for the moment. How I play it – how I re-create the music – is creative. The composer may indicate ‘pianissimo’, but how soft, or ‘allegro’, but how fast?”

Okay, I thought. That made sense. No two actors or musicians will give the same performance. Creativity and re-creativity both require skill and imagination and individuality.

Then I thought of my research, and how I worked on the same problem for years, and gave similar lectures using the same illustrations repeatedly. Each time I saw something different and made small additions or deletions, or modified the tone and direction of the talk.

What about sports, I wondered.

This week I have been engrossed watching the NBA basketball finals (Golden State Warriors vs. Cleveland Cavaliers) and the French Open Tennis Championships. Seth Curry and Kevin Durant of the Warriors, and LeBron James of the Cavaliers, among other stars, are indisputable artists of the highest caliber. Their skill is mind-blowing, but equally important is that each player has a distinctive and completely original style; no one else has ever been like them on a basketball court. Similarly, the women’s tennis finalists of the French Open – Jelena Ostapenko from Latvia and Simona Halep from Romania – are unique artists, as are the men’s finalists, the extraordinary Rafael Nadal and his easily defeated opponent, Stanislas Wawrinka. The women’s winner, 20-year-old Ostapenko, ranked 47th in the world, defeated the more experienced Halep, ranked second in the world, in a major upset. What an interesting match!

But it wasn’t the victories of Nadal and Ostapenko alone that made the matches special and creative. There’s always a winner and a loseer. No, I believe the creativity lay in their unique voice: the details of their strokes, their footwork, the way they cover the court and their strategy. All tennis champions differ from each other, yet they have all won the same tournaments with skill.

When I played tournament tennis as a teenager, I was always able to identify a player in a far-off court by their strokes and movement, even if too distant to recognize their face.

“No matter how many times I play a composition, it’s never exactly the same.” – Gregor Piatigorsky

The unique movements and style of athletes are a critical part of their performance art and creativity. Aren’t these traits the same as ‘voice’, an indispensable feature of creativity in general? We recognize from a distance the work of Monet, Rembrandt and Picasso because they are distinct, even if we never saw that particular work.

And here’s the remarkable thing about voice. When I tried to imitate the great tennis stars that I admired in my teenage years (Pauncho Gonzales, Frank Sedgman, Ken Rosewall), my game improved, but I never came close to resembling them. What was in my head and what was displayed by my tennis had nothing in common, and I knew it. Voice is unique and cannot be replicated by anyone else.

It’s all about voice – expressing who you are by mastering the choices you’ve made – and it can start very early.

Which brings me to my 13-year-old granddaughter. I traveled to San Francisco a few weeks ago to see her perform in the Fracas Circus, as a tissue artist. Watch the attached video to see her performance. She has been working seriously for at least five years, perhaps a bit longer, to achieve this impressive skill. When she looked at my video after her performance, she immediately pointed out what she did well, and what she thought was a bit too slow, or what she might have done somewhat differently. I sensed her involvement. She’s a creative artist in progress.

Leave A Comment