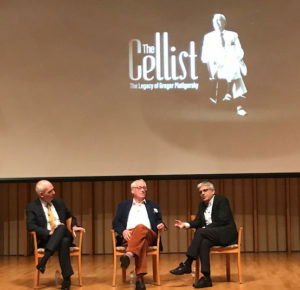

(Left to right) Sel Kardan, Murray Grigor and Hamid Shams, creators of the movie.

The Colburn School, a school of the performing arts in Los Angeles, recently featured a preview showing of The Cellist: the Legacy of Gregor Piatigorsky. This beautiful movie, masterfully done by Murray Grigor and Hamid Shams, dovetailed with the viewing of my father’s Archive exhibited at the event. The movie impressed everyone attending, which included a number of my father’s students who have built notable careers since his death 42 years ago. One member of the audience said to me after the movie, “I have a new hero.” Papa, a cellist, raconteur, writer and teacher – an artist at heart – had a remarkable life and legacy. As always, I was proud to be his son.

The timing of the movie was fortuitous for me, since for the last few years I have revisited my own life by writing a memoir, The Speed of Dark (Adelaide Books, 2018), which can now be purchased on Amazon. Looking back at the completed memoir, including my childhood, education, science, collecting and writing, I am struck by how much I have omitted. True, the events and stories I write about are factual, as they are in Papa’s movie. They are all documented, yet, like any biography or historical account, they do not substitute for the life itself.

No matter how well researched, a movie or book is a story with an autonomous existence and cannot resurrect the layered complexities and conflicts of a human being. Nothing I write about an event fully recreates what I felt at the moment of, or before or after, the event. Moreover, what I felt in the past cannot be assumed to be the same as its memory in the memoir, for although I am the same person, I’ve also changed throughout my life’s journey. In general, the challenge of a memoirist or biographer is weaving a private inner life with the events themselves. How, for example, to impart stage fright to an audience?

The private, inner life makes me wonder to what extent our personal identity reflects our ultimate legacy: who or what determines who we are?

Consider the establishment of a scholarship fund. How the scholarship is used by, or its effect on, the recipients does not reflect whether the donor scraped the bottom of his or her finances to establish the scholarship driven by devotion to the cause, or whether he was a billionaire who established it for a tax-deduction. Never mind: the scholarship becomes a worthy contribution that sheds a positive light on the donor’s identity and legacy. The donor has established a scholarship that bears his or her name.

Is it the act or the feelings and reasons behind the act that determines who we are? The act, after all, is the only concrete record we have. Is a death-defying action to save the life of a wounded soldier in battle equally heroic if performed by someone despite being desperately afraid for his own life, or by someone without fear driven by dreams of heroism and self-aggrandizement? In either case, the person did save a human life and receives a medal of honor.

A sculpture of my father on display at the movie premier, made by my mother.

These esoteric questions may seem like my mother used to call “a typhoon in a teacup.” Of course, no one event determines a life, identity or legacy, and it is self-indulgent to consider one’s own legacy. However, when facing a blank computer screen while writing a memoir, I constantly struggled with multiple feelings, at times contradictory, as I described the events to tell a story of who I am. To what extent was I more artist than scientist in the laboratory, or scientist than author when writing a novel, Jellyfish Have Eyes, or re-enacting my lineage when collecting Inuit art. I never felt I was entirely one person. The flood of memories while watching The Cellist or writing The Speed of Dark made me think that it would take more than one movie or memoir to represent the interacting and autonomous inner and outer lives.

We are, I suppose, both inner and outer people, in different ratios depending on who is telling and who is listening to our story. No one version can claim absolute truth, which makes each life endlessly rich.

Dear Joram,

Is the documentary available for putchasr?

Best Regards