Traveling on vacation, temporarily escaping the monotony of the familiar, easing the burden of responsibilities, riding air currents far above traffic jams and local politics is intoxicating. Thus, a five-week boat tour up the west coast of Africa advertised in a National Geographic/Linblad Expeditions catalog caught my attention. The tour began in Cape Town, South Africa, where we would board the Explorer, and ended in Morocco. The journey encompassed 6,500 nautical miles. Much too long, I thought, but yet . . . the west coast of Africa? Intriguing. I toured Egypt and Morocco a few years ago – fascinating countries – but I had never visited sub-Saharan Africa, and I had never even heard of Togo or the tiny countries of São Tomé and Príncipe that were on the itinerary. Apart from its intrinsic interest and novelty – I generally prefer a new meal rather than yesterday’s warmed-up dinner – here was an opportunity to visit the origins of some of my collected African tribal art comprising mainly staffs, figures, metal works and textiles.

No less important, the mystique of Africa – the evolutionary birthplace of Homo sapiens – had a romantic flavor titillating my imagination and propensity for story-telling. I doubt that many of us from the highly developed United States, including scholars and collectors of African art, have much first-hand knowledge of this vast continent. Most tourists of sub-Saharan Africa target safaris and wildlife, thinking of Africa more as a vacationland than the complex, diverse continent that it is. The advertised National Geographic trip was about the culture of West Africa and included sixteen different countries (seventeen if one considered Western Sahara separate from Morocco); Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ivory Coast, Guinea and Mauritania were skipped for safety, political or other reasons that were not revealed.

I asked Lona what she thought of going on this trip.

“Africa?” Her tone said it all. “Isn’t it dangerous? The newspapers are full of reports about pirates and kidnapping. The Arab Spring. Al-Qaeda. I can’t keep it straight! What if we get sick?”

“The pirates are mainly along the east coast, especially Somalia,” I countered, ignoring everything else. However, I read the newspapers too and shared her concerns. But still I wanted to go. I remembered visiting Tel-Aviv and Jerusalem, bustling with normal daily life although the Palestinians were sending rockets into Israel along the border and terrorists were sporadically bombing buses and cafes and marketplaces. Two years ago we went to Jermaa el-Fnaa Square in the center of Marrakech in Morocco, a month after a bomb attack, yet it was crowded with peaceful activity. What to believe? What do the African newspapers report about the shootings at the Sandy Hook school in Connecticut or in the theater in Aurora, Colorado? Would those massacres prevent an African from visiting the United States?

“I’ll try to find out more about the trip,” I said, sensing Lona’s fears more than lack of interest. I called National Geographic and they told me that the better cabins were already booked although it was almost a year in advance. The popularity of the trip whetted my appetite and I figured that I’d better sign up immediately before I missed the opportunity. The lure of the hard-to-get! I felt confident that Lona would come around. In any case, it wasn’t an irreversible commitment. We had five months left to withdraw without penalty. I reserved one of the available cabins on the Explorer and added our names to the waiting list for better accommodations, just in case we decided to go.

Collecting African art left me wanting to know more about the continent.

The reservations, although tenuous, elevated the African trip from an abstraction to a plan, and the more I thought about it the plan boosted another notch to an adventure. It was then that I realized that this wouldn’t be just another ordinary holiday but a personal challenge to re-examine my lifestyle, the values of my privileged life, and the luxury accorded by freedom and money. I have had the enormous advantages of being born in the right place and the child of the right parents. Lucky me! How about much of the rest of the world?

A few weeks later National Geographic called to say that they had a cancellation for one of the larger cabins. It was expensive, but I said yes. Lona was getting excited now too. Let’s be comfortable, we thought, five weeks is a long stint. Interesting how a chance mailing, an impulsive reservation and a cancellation can affect one’s life.

We were scheduled to explore the Atlantic coast of Africa, an area of the world I could only imagine. We got the required Yellow Fever inoculations, malaria pills, and antibiotics (just in case) as well as extras of our daily medications (cholesterol-lowering pills, blood pressure pills, vitamins) and everything else we could think of. It was as if we were heading to a different planet. It was Africa, after all, the distant land of wild animals and tribal cultures.

When the time came we overstuffed our duffel bags with enough clothes for months if not years and loaded our “carry-ons” with our passports, Euros and dollars, cameras, cell phones, laptop computers, books and nooks and what-nots, and embarked into the great unknown.

At first glimpse Cape Town looked like any modern city with shopping malls, residential areas, restaurants, hotels – the usual – however waiting for the baboons to cross the street when driving to the Cape of Good Hope, or stopping to gaze at the wild ostriches strolling along the beach or at penguins nesting by the roadside were outside of my ordinary experiences. My camera clicked away as if I could take the atmosphere home with me simply by capturing visual images, or perhaps I was eager to prove that I had really been there in order to add another notch to my collection of countries that I had visited. No, my cynicism is skin-deep and shortsighted. I recognize the difference between a first-hand experience – witnessing – and a second-hand experience of reading or being told.

Cape Town, as viewed from Tabletop Mountain

Witnessing, in a sense, cracks open scenes just enough to let the observer slip in, if only for a few moments, and sets the imagination in motion enhancing the impact. Witnessing is analogous to showing instead of telling in a novel. Furthermore, associating what one sees with previous, resonating experiences gives it personal meaning, making the trip add to the overall structure of one’s life. One might say that going on a trip is the difference between making a movie instead of watching one, or at least thinking about making a movie. Recall for example an event that you have witnessed, such as perhaps a car accident that resulted in a serious injury. Now consider an earthquake or an act of terrorism that killed multitudes in another country that you may have heard about in the media. Terrible atrocities. Catastrophes and human suffering that reach us second-hand affect us, but more intellectually than emotionally. They shrink to passing flags in the parade of life, but they do not stamp indelible, lingering impressions. The power of sight – witnessing – blends one’s soul with the scene. It sucks the outside in.

I felt the impact of being there when visiting Victor Verster prison in Cape Town, a minimum security farm prison where Nelson Mandela, the great liberator and statesman, spent the last three of his twenty-seven years of imprisonment. Before that he was in the maximum-security prisons on Robben Island in Table Bay near our hotel for eighteen years and subsequently in Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town for six years, neither of which we visited. Today Mandela’s imposing statue marks the entrance to the Victor Verster prison, a paradoxical sign of honor. After it was known that he was destined to be the future President of South Africa, he was moved to a furnished house on the premises of the prison. Imagine the irony of a prisoner idolized as a symbol of hope for a better future, probably living more comfortably than the guards, and drafting the future political foundations of South Africa with President F. W. de Klerk. Even so, he was monitored continually and denied having even a family member as an overnight guest. What strange history!

Our prison guide, a long-time guard, glowed with pride as he told us how he had shaken Mandela’s hand on more than one occasion when he was a prisoner. Those handshakes and few remarks that transpired between them remained a centerpiece of the guard’s life even twenty-three years after Mandela’s release. The universal need for a hero such as Mandela or Einstein whether in good times or bad, never ends. Regretfully, however, that need also contributes to the rise of heinous dictators such as Hitler or Stalin. Listening in Mandela’s prison house to the guard talk to us about his experiences with Mandela, sitting in Mandela’s chairs, imagining the intangible transfer of humanity from Mandela to me through the guard’s words, gave me chills and awoke an emotional response that I never would have felt if I hadn’t been there. This spark of lingering hope begging to be fanned in war-torn Africa, a continent still bleeding from its many wounds that heal slowly at best, impressed me deeply.

And then there is the history of slavery when countless innocent souls, many mere children, were kidnapped and shipped like cargo to Brazil, the Caribbean islands, the West Indies and the United States. There were many sites that turned into experiences that I won’t forget: Cape Coast Castle in Takoradi, Ghana (where President Obama unveiled a plaque on July 11, 2009) and the “House of Slaves” on Gorée Island in Dakar, Senegal, both World Heritage Sites; the dungeons where the captured Africans were squeezed like sardines in a can before being shipped out; the signs specifying which dungeons were for men and which for women and children (there were separate cells for women, jeunes filles, and children, enfants, in Gorée Island). The stories of slavery became palpable when I felt the heat, saw the tiny, lightless spaces hardly fit for an animal much less a human being where captives were punished for weeks and months for virtually nothing, and when I traveled the same road that the slaves trudged and circled a tree meant to “erase” their memory of home as they made their way to the Door of No Return.

I’m reminded of when I visited Alcatraz prison in San Francisco and volunteered to stay alone for less than a minute in a windowless cell used for solitary confinement that was much larger than the pitiful holes used for the African slaves. Oh, my goodness! When the door clanged shut and enclosed me in such blackness, I had no sense of whether I was in a coffin or outer space. The silence was thick and heavy. What a terrible experience! How long would I have survived as an African slave stuffed into one of their prison pits? I fear not long, but I have never been tested. Once again: lucky me! But some of the slaves did survive as nameless heroes that drifted into the mass of humanity known only as “them,” those that were not born in the right place at the right time as I was. They endured great hardships and displayed enormous courage. Choice in life has its limitations. Praise or blame is not always earned to the same extent in different instances.

It remains difficult at best to witness with objectivity not tainted by prejudice that sneaks up without warning. For example, Lona and I were exploring a section of Cape Town selling local carvings, textiles, jewelry and various handicrafts sprawled out on the sides of the street. Since this was our first exposure to aggressive salesmanship by the locals (which was slight compared to our experiences a few years ago in Egypt), we had no idea how tempered it was compared to what was to come in the more impoverished countries. Many items were tempting to buy, but we tried to refrain since we had a long trip ahead of us with many more opportunities. We continually said no thank you, yes, the mask is very nice but no, not now please, and so on as we made our way along the street, taking pictures as tourists do. Always taking pictures.

What pests, these sales people, I thought, yet there was something heartbreaking about them, They seemed so earnest, their eyes so imploring. The difficulty for them to earn a living with all the “shops” offering similar items seemed unimaginable to me. “Please, I haven’t sold anything today. Only one dollar. How much will you pay? I give you good price!” A hard-core realist may not be moved by such manipulation, but I’m a soft touch. I bought textiles, a stone soap dish, a beaded necklace, a wooden salad bowl, and a few other souvenirs. I shook hands with the successful merchant after each sale, and he never failed to smile radiantly for his photograph. Was this a genuine connection or contrived? What was his economic or social status? Had I made a difference? Did he have a family or children? What were his thoughts about me, a white American tourist presumably with more money than he could imagine? Never mind. I had it all digitized in my camera!

The trouble began when I returned to the hotel carrying my purchases in several bags and sat down next to a fellow passenger and his wife in their late sixties or early seventies cooling off with beers in the air-conditioned lobby. I had not met either of them yet.

Suddenly I felt self-conscious – embarrassed – that I’d bought too much, that I lacked discipline and had done something foolish that I needed to justify. I looked at my bags of souvenirs and volunteered, “I wanted to help these guys; they have so little.” Did they? How would I know? What’s little or much for the natives of South Africa?

After a moment the gentleman, call him G for Gentleman, said in what I discerned a judgmental voice, “You’re rich; you can afford it.” Harmless, certainly, and true too, as it must have been for him as well. No pauper would be on the same trip. Perhaps it was his tone, or at least how I interpreted his tone, but I found his unexpected comment strange, uncalled for and provoking. I should have brushed the comment aside with a silly response such as, “I wanted to buy a yacht but they were sold out,” or some other meaningless remark. But G’s comment resonated with my age-old self-consciousness of wealth, having more than most, having more than I need. Irritated, I retorted, “How rich do you think I am?” G answered my question with another question: “Oh, something like Rockefeller maybe?” Why didn’t I smile at my fellow tourist, who was certainly not a bad man? He knew nothing about me, or I anything about him. However, a surge of anger took command of my senses, and I said, “That’s a ridiculous question – idiotic – which doesn’t deserve an answer!” Childish, I know. I may have been a tourist in a foreign territory taking in the sights, but I was also the same person I was at home and trapped in the same brain. He didn’t say another word as I chatted with his friendly wife, who seemed unaffected by the exchange.

When I related the story to Lona she said, “Good for you.” I guess the person who tells a story gives it its flavor. I wonder what she would have said if G had given her his take on it.

The next day, our first at sea, G approached me on the deck of the Explorer and asked,

“How’s chemistry?” He was picking up on the brief discussion about science I had with his wife. “Fine,” I said, slightly perplexed. He then laid into me saying how offensive I’d been and looking self-righteous, said, “You were a smart-ass. I just wanted you to know that.”

Then he went on his way. Nice start to a trip together! Lona encouraged me to make peace with him. Good advice. When I found G alone in the lounge, I told him that I’d meant no harm and had foolishly overreacted. “Why?” he asked.

I stalled for a moment. I had no easy answer. How to explain to a stranger, especially to G after our unfortunate encounters, that South Africa had triggered a guilt feeling that I needed to give to those with less than me, not only for charitable reasons, but to avoid criticism, to justify having been born lucky, to be accepted. The knee-jerk rage that conquered my common sense had resulted from witnessing events through lenses stained with my own colors. Traveling was a caged freedom that distanced, if not insulated me from what I saw. “Being there” was a qualified “there.”

G reluctantly shook my outstretched hand, but he did not speak to me or look me in the eye throughout our five weeks together on the ship. I suppose he was in his own “there,” as we all are, and which strains our efforts to truly understand and empathize. This ridiculously minor event with G, inconsequential, so potentially easy to have moved beyond, persisted like droplets of poison in the tropical air we both inhaled in the comfortable ship.

Consider now the history of the Africans and the hardships endured. They were suppressed by European colonists, sold as slaves and massacred in brutal civil wars. Now fast-forward to the present day countries we visited, where they are striving to forgive one another to forge a peaceful future by putting the atrocities behind them. They socialize with the very people who had raped and slaughtered members of their families. Meanwhile, G and I, tourists from the developed United States, living in freedom and luxury, nurtured our grudges and struggled to even acknowledge each other. How relative it all is, and how difficult to puncture the tiny soap bubble in which we float.

Most of our shipmates had traveled extensively throughout Africa and were regulars on the Explorer touring other places. Few failed to ask us how many trips we had taken on that ship. “This is our first,” we answered. “Oh, you’ll love it. We’ve been on seven (often more) trips,” was the typical response. Professional tourists, I thought, awakening a prejudice, thinking that they must be bored to death collecting destinations, exclaiming how fascinating it is, how broadening and the like. Was it necessary to roam the world seeking interesting things, I wondered? And then I asked myself how much experience can one truly gain by being spoon fed – entertained – by such tours, traveling in buses and peer groups and a luxurious ship. Does a spectator learn much about the animals in the zoo or experience crime watching a movie about the Mafia?

Stop! I commanded myself, knowing that my wave of negativity was paper-thin and porous. For every argument there was a counter-argument. I resigned myself to absorbing what I could. And there was much to absorb: a variety of urban and natural landscapes in the different countries (deserts, savannahs, rain forests, jungles); a sidewinder snake burrowing in the Namibian desert sand; a chameleon moving one eye at a time scrutinizing the surroundings; flamingoes feeding by the seashore; goats climbing trees (really! in Morocco); different European architectures left in place by colonists; houses in brilliant shades of primary colors; striking braided hairstyles on infants and children and young girls; women draped in dresses and men in shirts with exotic patterns in dazzling color (Africa is color!); modern sport stadiums built by the Chinese (in contrast to the limited presence of the United States); opulence and poverty side by side (more of the latter than the former); open markets; trash heaped upon trash; Africans and their families on Chinese motorcycles swarming everywhere; groups of unemployed people sitting around, drinking, speaking on cell phones, waiting (for what?); lines of empty taxis in crowded cities with not a tourist in sight (who goes on these taxis?); endless rows of shops in the open air selling trinkets, tires, used furniture (you name it); the fetish market in Ouidah, Benin selling shriveled, dead animals, skulls, bones and other magical objects of the native animist voodoo religion; hair “salons” in dilapidated shacks; signs of God and Christianity and AIDS on billboards and houses along streets needing repair and littered with potholes and gravel; rhythmic drumbeats and dancers on stilts greeting our ship at the docks and in public places; Ganvié, a fishing village built on stilts in the center of Lake Nokoué in Benin; a short trip on a pirogue (dugout canoe) up the Lobé river near Kribi, Cameroon, to see tall Bagyeli “pygmies” pretending to live in the forest for the benefit of tourists; uniformed officials boarding our ship at each port for a passport face check and eager to accept gifts; police escorts for our buses (why?). Four of our own security guards armed with rifles patrolled the ship day and night insisting there was no danger as we traveled up the coast. These are highlights.

Our voyage was as much an intensive college course as a vacation. In addition to sightseeing, we listened for hours to lectures on the Explorer given by hired professors and guides specializing in African history, economy, sociology and linguistics. We learned about the hundreds of languages spoken in each country, many going extinct. There were also lectures by the curator of African art in the Seattle museum, a geologist, a birder, a botanist, a biologist and an ethnomusicologist. Ambassadors to African countries, and even the former president of Ghana, J. J. Rawlings, were invited to address us on the Explorer, and we danced to African music with a strong South American flavour derived from slaves who returned from the Caribbean. Africa defines diversity, complexity and upheaval. It’s easier to think of the stereotypical lions and giraffes grazing in fairy tale settings, and the tribes with their Chiefs and hierarchy continuing their ancient customs. Those romantic aspects of Africa exist as well, adding to the scenes we observed as we tried to untangle their layered nature.

While the urban areas bustle with activity and cars and motorcycles and shops, rural villages of yesteryear exist a few miles beyond. We visited a Ewe village in Lomé, Togo that put on a spectacular durbar (an English word derived from an Indo-Persian term for “ruler’s court”) for us as they might have generations ago. This hierarchical celebration with native music and dancing had the village Chief and his Queen in the center of activities surrounded by underlings and the Chief’s spokesman carrying a gold-plated staff.

Royal paraphernalia reflecting wealth and status was showcased. This Chief, so important and revered in his tribe, no doubt had an ordinary position in the nearby city, perhaps in a store or as a local official of some kind. Similarly, many Africans practice an official Christian or Moslem religion in town, but then turn to their ancient native animist, voodoo religion for their private, deeper beliefs. These parallel lives with one foot in “official” customs and language (English, French or Portuguese, depending on their previous years of colonization) and one foot in their ancient, tribal traditions and native dialects add to the complexity of African society. The original, native languages of the particular cultures overlap the arbitrarily chosen borders made by colonists, creating conflict between national and tribal loyalties.

Visiting the origins of African art was one of my motivations for going on this trip. Tribal African art – incorrectly considered primitive by some – exists in museums and collections throughout the United States and Europe as extraordinary examples of artistic excellence, creative abstraction, high technical achievement and originality. African art has influenced artists worldwide, with Picasso being one of the most famous. Ethnic African art is mesmerizing. Disappointingly, however, except for some textiles, the torrent of art I saw in Africa was ordinary and stamped out for tourists, a stark contradiction to the paucity of tourists in the locations we visited. Reproductions (some very nice) abounded in shops and the streets. One gallery in Dakar, Senegal – La Galerie Antenna operated by a Frenchman (Claude Éverlé) – did have a number of excellent art pieces, but this stood alone. I bought a Nigerian stool, an Angolan stool and a Duala Cameroon staff. It seems that little of the outstanding art of sub-Saharan Africa remains in its place of origin. What sad exploitation. However, current artists continuing the tradition of imaginative and skillful expression are scattered here and there in the countries we visited, even in the impoverished townships.

Amidst all this variety and complexity, there are masses of children with smiling faces and bright eyes sparkling with life and energy. Lines of kids waved excitedly as we rode by on the train (built by the Chinese, of course) in Angola from Lobito to Benguela, as they did in the other countries. Children from a few months to young teenagers were in the streets, on the beach, on fences, playing with each other, being carried on the backs of their mothers or older sisters (occasionally fathers and brothers). Kids that seemed no more than eight or ten years old were fishing on their own in rickety boats (getting the evening meal?), sweeping floors or doing some other task if they were not just hanging out in groups. The children loved to be photographed and showed off for the camera. They were eager to see their images on the digital display, especially the young ones. The children are clearly a valuable resource for the future, however the sparse schools with few amenities and high expense for education create formidable obstacles.

In contrast to the children, the adults often hid from the camera or became angry if photographed. On occasion they threw rocks or sticks, protesting the invasion of their space, refusing to be treated like animals in a safari and protecting the integrity of their souls from being stolen by the camera. I found it hard not to sympathize with them, for who wants to be a spectacle for amusement? Yet, conflicted, I continued to photograph as discreetly as I could (luckily I had a very small camera), and made an effort to communicate with them before taking their photograph or pay them to pose, although a posed image is seldom as interesting as a candid one.

Regardless of the country or the specific activity in which the children were engaged, I can’t remember a child whining or appearing disgruntled. I remember only one or two instances of a baby crying. How different from the scenes I am familiar with at home, and our expectations of children in general. Expectations are critical to accomplishments as well as to what we think we ought to see. I noted myself taking an abundance of photos of townships, scattered trash, poverty, women balancing heavy loads on their heads, and tribal affairs. Was that what I expected to see? What did I miss that was hiding before my eyes, the unexpected? What would a native African choose to photograph in the United States: skyscrapers, parking lots packed with expensive cars, grocery stores?

As I strived to digest all this I had to remind myself that comparing cultures, especially by a naïve tourist such as myself, is analogous to interpreting what two people speaking a foreign language are telling each other by looking at shadows of their body language. For example, these very same children that charmed me had other sides suggesting a very different story. There was an instance when I was strolling on the beach where fishermen were repairing fishing nets and tending their small canoe-like boats. I slipped, causing my hands and camera (that was more serious!) to be smeared with wet sand, so I went back to our van parked close by to get a water bottle to rinse away the muck. A small band of alert kids followed me. When I cracked open the sliding door of the van the children transformed instantly into an unruly pack heading for the van.

“Stop,” I said. “What are you doing? Go away!” They ignored me as they rushed into the van, triumphantly grabbed every water bottle (nothing else) and bound out as quickly as they entered. They poured out the water, laughing, delighted with their acquisitions, and ran off. Were they going to use the empty bottles for a game of sorts, or cash them in for a few pennies? I had no idea, nor did anyone else I asked.

These nameless children are valuable resources for African nations, as are the deposits of oil and minerals, but significant obstacles exist to reduce corruption and raise the standard of living. The fates of these nations seem in jeopardy and depend on serendipity as well as education, which is replete with challenges. Tourists are among those chance events that could make a difference. Staff members on our trip brought school supplies for the children. One passenger had served as a volunteer and contributed to a hospital. Another couple on the trip had joined an organization that led to their support of a child whom they visited from time to time and whose life they enriched. Lona and I contributed to an organization that combated illegal fishing off the coast. So much more needs to be done.

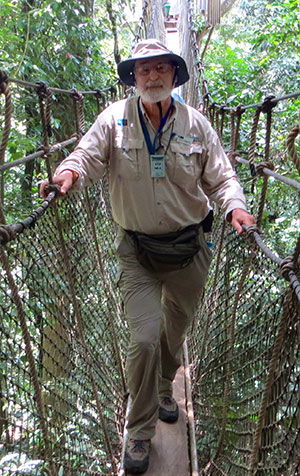

A walk above the trees

Exactly what, then, was I looking at as I cruised through coastal West Africa clicking my camera here, there, everywhere that caught my attention, feeling frustrated by my inability to penetrate beneath the surface? I felt like Chevy Chase in his classic movie farce, Vacation, saying, “Amen, let’s go,” as he stands on a ridge overlooking the Grand Canyon. Perhaps when it is too overwhelming that is all one can say.

Although the trip was educational and rich food for thought, I felt insulated, both physically and culturally separated from the pulse of what was there. My crossing single file across the seven canopy walkways suspended atop the rain forest in Kakum National Park in Ghana serves as a metaphor for the voyage from my perspective. Countless hidden wonders hid beneath the narrow bridges that wobbled precariously above the trees. The landscape was picturesque and photogenic. I had the thrill of being there, smelling the fragrances, hearing the bird calls and rustle of leaves, sweating from the tropical humidity drenching my shirt, even seeing (and avoiding!) a deadly green mamba snake resting peacefully on the railing of a bridge. Yet the high rope sides protected me from any danger of falling into the forest. Possible danger was a figment of romantic imagination, as grasping the cultures and lives of the Africans was an illusion.

Whether insulated or not, real or illusory, Africa opened my eyes to how limited my experiences in life have been. Inside the mind of each stranger in the street or local guide or drummer or merchant or child or tribal chief exists a mysterious universe and network that I know nothing about, every bit as complex and interesting as my own. Janet Malcolm expressed this sentiment well in her essay, “A House of One’s Own,” about the Bloomsbury legend: “No life is more interesting than any other life; everybody’s life takes place in the same twenty-four hours of consciousness and sleep; we are all locked into our subjectivity, and who is to say that the thoughts of a person gazing into the vertiginous depths of a volcano in Sumatra are more objectively interesting than those of a person trying on a dress at Bloomingdale’s?”

Many truths rattle within the background noise. The challenge and reward rest in finding the one that relates to you.