My father the cellist was a tall man. He held his Stradivarius cello high with his arm extended and his hand gripping its neck as he bounded onto the stage to eager audiences, adding height and depth to his image. It was a glorious sight. People say he played like a God. I can tell you it was inspiring the way the sound flowed from the soul of his cello, enveloped by his bear-like body, his eyes closed, his head tilted towards the scroll.

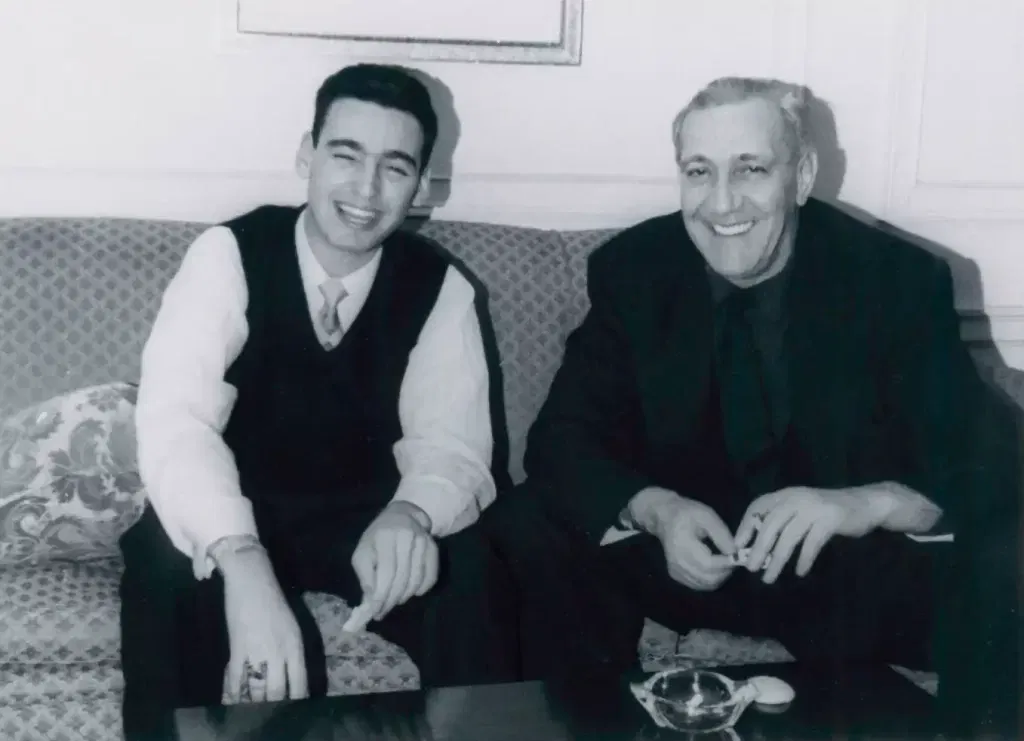

Between college semesters many years ago, in the early 1960s, I accompanied my mother and father at the Casals Music Festival in Puerto Rico. Casals was a very old man then, in his 90s, but still active. My father was scheduled to perform at the festival. It was hot in Puerto Rico and we swam at every opportunity. While at the beach, my father and his friend, the conductor Zubin Mehta, had an inspiration to play the Don Quixote cello concerto by Richard Strauss that was not on the formal agenda of the festival. The spontaneity of it all, with wet bathing suits and half eaten sandwiches between concerts, was like Don Quixote himself appearing from nowhere in a shiny coat of armor ready for battle with no military strategy. But the idea took hold: A phone call from Mehta to his father in California to send the music express, an impromptu rehearsal the next day, and then the concert.

I sat amongst the audience, one of the throng but so different. I tapped my fingers self-consciously upon my knee and watched the empty seats disappear. I felt anxious, although I did not know why. Soon all the seats were filled, extra chairs were placed on the stage, and TV cameras were strategically placed for local broadcasting. The whole island was preparing for this grand event. Then out my father came from the side of the stage, cello elevated. He walked across the stage and claimed the featured chair upon a small platform in front of the orchestra. Mehta stiffened slightly preparing to conduct. Applause, and then a great hush, heavy as the humidity.

“In the Audience” first appeared in the literary journal, Lived Experience.

Download a PDF of In the Audience.

Read more: Joram’s Lived Experience Essays

My mind drifted in the few seconds of quiet before the music began, and I thought of my father marching on the stage behind his cello. To me he looked imperious, as if the world was under his command: A King on his throne. I remember this image fit the scene, but why then had he been so nervous, so irritable before the concert, so much so that we shied away from him? And why, I wondered, did he raise the cello above his head? Was this just a bit of showmanship, his trademark so to speak? Perhaps, at least in part. I thought no more of it at the time. But now it’s not so clear to me. I know he idolized Stradivarius. I wonder whether he held the cello high above his head as he walked across the stage to place it in the clouds, above the heads of mortals, or was he just protecting it from being knocked, or most interesting, was it part humility for him to walk below? He said so many times that he was just a servant, that music was larger than any man, and that he was chosen by the sacred cello, not the other way around. If I have learned a thing or two, it’s that not all is always as it seems; each story has many strands waving in the breeze of thoughts, shifting directions with the wind and time.

My father scanned the audience as he sat upon his chair. My mother and I were in the audience along with a sea of strangers, a speck in the anonymous public. But suddenly I felt that I was also on the stage, in my mind that is. My genes were on the stage, and I was apprehensive once again, as if a great responsibility lay on my shoulders. How disoriented I’d felt to be my father and myself as well!

Gregor Piatigorsky plays Finale from Don Quichotte (Strauss)

My father projected confidence in the moments before the music started, and I assumed that he felt ready and entitled to treat the world with his gift. I felt proud for him and me. Despite the fears he showed and spoke about at home, I knew that he knew his strengths. But as he sat upon the stage before the audience, waiting for Mehta’s sign to start, I imagined him thinking, “What a crazy idea to play the Don Quixote concerto, unprepared, on the spur of the moment.” I thought about his run-away enthusiasm that so often poured from him, like his dreams – more correctly illusions – of exploring jungles and searching for burial grounds of elephants, or roaming the oceans or arid deserts to witness their mysteries. Yet, I knew, as did he, that he would never act on these dreams. He had often told me how lucky I was learning so much at college and how I could have such adventures in my life. It was almost as if he envied me! I wondered whether he expected me to live his dreams. And if I did, did he believe my life would be enough in the jungle rather than on a stage of sorts? Did I believe his dreams would be sufficient for my life? The thought returned that we shared genes, he and I. And then I wondered whether he’d felt that part of him was in the audience with me, as I’d felt part of me was on stage with him. Mehta lowered the baton and the orchestra commenced. My father joined the music with a bold bow stroke. He closed his eyes and swayed and made Don Quixote roam the stage.

The noble Don – my father’s cello – talked to Sancho Panza, charged the famous windmill, and fantasized his love of Dulcinea. I too closed my eyes and thought of Don Quixote, bringing more confusion still. I was, simultaneously, my father on the stage, praised and famous artist; Don Quixote, immortal idealist with dreams and illusions larger than life; and myself, college son, spectator, unknown, feeling both big and small, just me, alone.

Suddenly I saw my father’s face grow taut as the music paused. He tightened the bow hairs, wiped his forehead, and shifted his feet and cello. My anxiety returned. I remembered all the times I woke at night, scared of a nightmare that I was on the stage and forgot the notes, even though I never played the cello or any other instrument. The feeling of this dream returned full force as I sat in the audience: Had my father forgotten his notes too? His voice resonated in my mind.

“I’m not good enough,” he said. “Is anyone?” I’d heard him pose this question many times.

Although I sat still in my seat, my mind wandered without repose. I imagined him saying to himself, “I can’t recall exactly what comes next. I’ve played this piece a thousand times, even discussed it with Strauss himself (this was absolutely true); now I can’t remember all the notes. It would be terrible if I messed up, especially before my son. No, it would be worse than that: it would be a tragedy.”

Might these have been my father’s thoughts, I wonder now. Perhaps they were my mother’s. She’d suffered through my father’s fears. Also, she too was a performer, a chess champion and tournament tennis player, and knew the difficulty of public exposure. I remember feeling her tension, as I always did, as we sat together. Is it even possible to untangle these webs of thoughts and feelings?

Then the music resumed, exactly as it was supposed to. All was well and I relaxed again. I can’t believe I ever really thought that my father was mixed up or would not succeed. Even if he had a transient lapse of memory as he sat upon the stage in all his glory, the world his pawn, few if any would realize, certainly not me. He’d stressed so often that he was a survivor, and it was true. He survived the Russian pogroms when a little boy, and Lenin and the Bolshevik revolution, and then the atrocities of Hitler and Jewish persecution. All this was clear to me at the time and made me wonder what had I survived? Nothing came to mind. I felt my life had been conventional at best; I had no special conquests to proclaim or dangerous threats that I cleverly evaded. It seemed that I was destined for the audience and not the stage.

I had no answer to this thought, no counter-argument. I settled back and listened. My father’s cello tones filled the auditorium as they did my heart. The dying, final phrases carried Don Quixote to a beautiful death, satisfying and complete. Sancho Panza faded into the background. The battle’s over, I thought, at least for Don Quixote; no more windmills to combat, no more demons to avoid.

My father’s eyes remained closed; Mehta sighed. The audience was suspended for an interminable moment, time enough to swallow and let the final delicate morsel digest; applause erupted, then whistles and a standing ovation.

The concert had exceeded my expectations. Strauss would have been satisfied for sure; Cervantes would have been impressed. The audience was spellbound. I was mesmerized. My father sat still as death.

“Bravo!” echoed throughout the theater. I was on my feet, not on the floor but on a cloud, applauding. Shouting bravo was too conspicuous for me, too self-serving, like announcing I’m here too. My father wiped his brow, stood and bowed. He hugged Mehta; Mehta hugged him back. They were bonded, physically and spiritually. It was an exclusive affair that no one could penetrate: no friend, no spouse, no child. The circle was closed. He was my father, I was his son; we shared genes, but he was on stage and I remained in the audience.

After the concert walking in the crowd I heard a man say, “Magic,” and his wife nodded in agreement. Magic, I thought, was too abstract. It had been more like feeding a hungry person that didn’t know he was starving. It was the miracle of our brains converting sounds to music. It touched our human need for story with grace, sending emotional chills down the spine as the thermometer pushed a hundred degrees.

I rushed backstage while the applause continued and arrived just as my father came off the stage.

I heard him say, “Zubin’s a genius” to me as well as to no one in particular.

“You played phenomenally,” I said. “Fantastic. Incredible.” Artists speak in superlatives. I wanted to be understood. I meant it, and more. The more part was harder to get across.

“Thank you,” he replied. “I hope you liked it.” I thought he meant it too.

He turned to the growing crowd backstage and drifted towards the center of the room as he greeted many friends and fans. My mother and I waited in the corner of the dressing room as admirers paid their respects, one by one.

I heard him saying, “M-i-l-i-c-h-k-a, kidkins, what a surprise! I had no idea that you were here.” And so on. That’s what it was like, backstage. It lasted a long time.

A lot of Russian was being spoken, his native tongue. I spoke English and some French, my mother’s native language, but not Russian. I wished I did. I was never taught and never taught myself, like my sister did, a bit, later in her life.

Some people saw me in the corner with my mother, waiting. Occasionally they congratulated me.

“Thank you,” I responded, reluctantly. I felt it then, but know it now, how maddening it is to have one’s accomplishments not recognized, and humiliating to be praised for those of others, even one’s own father’s.

“You must be proud of your father,” they said.

“Yes,” I answered, because that was true.

I watched the beehive hovering. I doubted then, and still do now, that he saw me waiting, watching, thinking. I wondered what my father might be thinking as he gesticulated with enthusiasm, laughed at jokes, hugged old friends and conquered new ones. Did he really feel like the King, with a capital K, holding court? Who were the jesters, who the noblemen? And if he did indeed see himself a King, I wondered why he complained so often about the profession or anguish miserably about the critics, his constant demons? He said that he loved music, but not the career, the life of musician. As I saw him conquer crowds and individuals with skill and charm, I also heard his voice within my mind: “Hotels, concerts, constant effort my whole life, since I was eight, no, six, who knows, who cares? And the critics, who can’t play a note themselves but dare judge me.” There you have it: he was both King and serf to me.

All this was very long ago. Yet, I can still imagine him sitting on the stage, his eyes closed and head against the cello scroll, his body moving side to side. I still hear the music flowing and marvel at it all, as did the public. I wonder now once again whether he’d felt me in the audience and might have thought while on the stage or at another time, “I must make Joram proud of me. I cannot fail. I know what it’s like to have a father that one isn’t proud of. I know that.”

And if he did think so, why didn’t he let me know? That must be another story – one when he was a little boy and his father abandoned his family for two years and then returned, too late to save his son’s respect.

Time passed as we waited backstage for the last few stragglers to leave. I saw my mother signaling my father that it was time to go, as she often did. ‘Yes,’ he signaled back, ‘I know,’ but then he spoke some more, and more time passed. We waited.

My mind returned to what I heard backstage from him, as if replaying the end of a movie I’d seen before.

My father said: “Zubin’s a genius.”

I answered: “You played phenomenally. Fantastic. Incredible.”

My father replied: “Thank you. I hope you liked it.”

Oh, I forgot to say, he touched my cheek before he turned to face the crowd.

The truth is I more than liked the concert. It was extraordinary, and I was proud to be his son. My father died thirty-three years ago as I write. Almost fifty years have passed since that concert and I still remember it clearly, that is, I remember how I perceived it then. Was what I put in my father’s mind less true than what I remembered in my own? How can I know? But I am sure he touched my cheek backstage before he turned away.