Mr. Mellows squirms his 6-foot 5-inch hulk onto a flimsy wooden chair. The low tabletop presses down on his knees. A bare 40-watt fluorescent light in the center of the ceiling flickers from the ceiling in the barren room; brown stains mar the blond, dusty hardwood floor. The gray paint on the walls is peeling. A cockroach lies belly-up near the warped door with an empty hole where the doorknob used to be. A dark cloud eclipses the sun, sharpening the relief of the crack in the glass pane of the curtainless window.

In a plastic-framed print on the wall, a young woman wearing a straw hat with a pink ribbon milks a Jersey cow in a barn surrounded by aspens bearing golden autumn leaves. Rocks with red and copper-green veins protrude from a creek.

A young reporter from the Front Royal Magazine sits across from Mr. Mellows. He centers his horn-rimmed glasses against the ridge of his nose and reviews his notes. It has taken him almost a year to arrange this interview with the Mr. Mellows of United Steel Corporation. He hopes a successful interview will improve his chances of being selected for a community events reporter by the Potomac Gazette – a more illustrious publication.

Mr. Mellows scans the room, scratches his neck and runs his fingers through his thinning hair. His eyes lock on the farm girl gripping the udders of the cow.

“Makes me envious,” he says, sweating in the July humidity of Washington.

“What’s that?”

“The print. Is that the life, or what? A sweet girl, countryside, nature.”

“Yes, sir. Know what you mean. Let’s get to work.”

The reporter reads his first prepared first question.

“Mr. Mellows isn’t your real name, is it? What’s your birth name?”

“That’s irrelevant, isn’t it?” answers Mr. Mellows. “I answer to Mr. Mellows. I made Mr. Mellows who he is.”

The reporter searches for a response.

“But, sir, people want to know more about you. Nobody even knows your first name.”

“First name, last name, middle initial. Big deal.”

Appearing slightly flustered, the reporter presses on. “My name is Bob,” he says.

“Just Bob?” asks Mr. Mellows.

“Ringling. Bob Ringling.”

“Related to the circus family?”

“Not really. Everybody asks me that. Gets annoying.”

“See what I mean? Why don’t you call yourself Bob Circling, eliminate the annoyance, Pick your own name.”

The reporter scratches his chin. “I thought I was interviewing you.”

“Yes, correct. But I’m not sure why. What have I done worth an interview?” Mr. Mellows asks with false modesty.

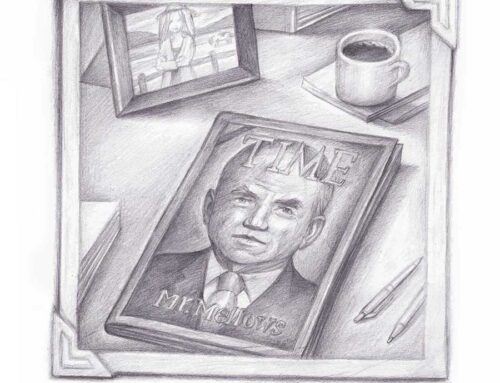

The reporter shakes his head. “You’re on TV, on billboards; there’s even talk of you being selected by Time magazine as the Man of the Year.”

“Ridiculous. I’ll never beat out Mayor Gargano. Do you know that his wife’s a Rockefeller?”

The reporter ignores the question and looks at the second question on his list. “The rumor is that your parents emigrated from Europe just before World War II.

Is that true?”

“Excuse me for switching the subject, but why is everything so run down here? The place looks like a war zone.”

The reporter clenches his jaw.

“You asked for a neutral site without publicity. You didn’t want me to come to your house or office or restaurant. A commercial real estate agent let me use this place. It’s a dump, but it’s the best I could do.”

“I like it,” responds Mr. Mellows, who finally reveals that he’s capable of smiling. He looks lingeringly at the farm girl.

“About your parents,” the reporter says, trying to refocus the interview. “Were they also in business?”

“Heavens no! My father was a molecular biologist, may he rest in peace, and my mother worked for a tree company.”

“A tree company?”

Mr. Mellows thinks a moment. “Yeah. She was tiny, only 4-foot 7, and loved to climb trees, heaven knows why. She didn’t weigh enough to break the small branches, so she was able to get to places that are hard to trim. Most of her work was on the estates of rich guys.”

“Pretty dangerous. Did it teach you to take risks like you’ve done in your work?”

“You bet, except that she fell off a tulip poplar by a tennis court on her fortieth birthday and bye-bye. I was 12. That made me the only child of a single parent. My dad told me to get used to it; nothing lasts forever. You might write that down. He was tough.”

“Wow! Quite an experience for a 12-year-old.”

The reporter scribbles ‘nothing lasts forever, tough father’ on his pad.

Mr. Mellows puts his left hand in the pocket of his gray cotton pants; coins jingle. He loosens his maroon tie and undoes the top button of his shirt, crisp white except for the symmetrical grey discolorations under his armpits.

The reporter wipes his brow. “Your father must have been a big man to have a tiny wife and a huge son like you.”

“Not really. He was about 5-foot 10 at a stretch. Don’t ever try to psyche out nature. It’ll fool you every time. Nothing’s predictable. That’s been a guiding principle of mine. You can write that down too.”

“Yes, sir.”

The reporter writes on his notepad ‘nothing’s predictable, guiding…’ He stops writing before finishing and looks lost in thought.

“Hello?” says Mr. Mellows.

“Sorry.”

The reporter asks another question.

“Was your father a well-known scientist? That is, were you exposed to fame as a youngster?”

“Hardly, although it depends on what you call fame. Most of the people in his building at work knew him, as did a dozen or so scientists around the world. He got an award once, from a pharmaceutical company. No, it was from an entomology society. He studied sticky stuff on the bottoms of the feet of certain kinds of bugs. I forget their scientific name. Busted his ass and sweated every detail of his work, and nobody cared, except a few peers. They argued like crazy as to who discovered what first. Man, it would make a boring movie! Watching him taught me a lot about life, even though it sort of broke my heart.”

Mr. Mellows hesitates. “Science is fascinating though. Something about it that’s…well…that rings true…” He looks sad and then adds, “Science doesn’t depend on perception to be right.”

“Is that what you learned from your father?”

Mr. Mellows checks his gold Rolex and then stares at the print on the wall.

“Mr. Mellows, what did you learn from your father?”

“Yes, yes. Excuse me. She’s so pretty. I mean, really charming. Like the girl with a pearl earring by Vermeer. Know that painting?”

“Yes, sir.” The reporter looks at the print and then returns to his question.

“About what you learned from your father. What was it?”

“Give awards, don’t get them. The percentage is much higher, and everybody else waits on the edge of their chair rather than you. Makes you far more important, and you don’t have to say thank you or grovel explaining how you don’t deserve it, that it’s all due to others, and…well.”

The reporter scribbles some notes, underlines a phrase.

“Mr. Mellows, how did you make USC so financially successful and innovative? The use of large sheets of pliable, green steel that’s comfortable to walk on, like grass, and generates energy from soil heat. That was brilliant! How did that come about?”

Mr. Mellows stands up and paces the room. He sneaks a look at the farm girl again, whispers inaudibly to himself and turns to the reporter.

“The first thing I did when I took over the company is strip titles from everyone. Hierarchy stifles creativity. It helped morale and ideas flowed like water. A green, soft, energy-producing woven steel grass substitute was just one of the ideas, and it came from a new recruit. Young people are too foolish to be cautious. You’re young. Know what I mean? Do you take chances?”

The reporter doesn’t answer. He asks, “Didn’t that create insecurity for the senior people?”

“Are you kidding? Equality is a great thing. It gives everyone the same opportunity.”

When the reporter hears “equality” and “opportunity” his eyes shine.

Mr. Mellows continues. “Everybody wins. I coordinated the show, like a…a….manager of a baseball team. Yes, that’s it. All the baseball players in the major leagues are great athletes. So why does one team do better than another? The manager, of course. He decides who does what, when, why. He’s the person who deserves the credit. That’s why managers are always getting fired if their team doesn’t win. The owners know that a different manager may make them winners. What an inspiration, a great manager! You can write that down in your notes. ‘Management is art’. Yes sir,” beams Mr. Mellows.

The reporter writes on his pad ‘management is art’. He also adds some comments to himself in messy handwriting with a disapproving expression on his face.

Mr. Mellows walks to the print and closes the fingers of his left hand around an imaginary udder. The reporter watches.

“It would be an inspiration to…younger people…to hear how you began such a successful career,” says the reporter.

Mr. Mellows gazes at the floor.

“My path to success? I never did or said anything that the majority didn’t agree with. Then I implemented it. No need to be a ‘lab hermit’ doing stuff that no one cares about. I never believed in originality by obscurity. It’s reverse snobbism. Listen to the voices out there. It’s like my garbage company.”

“Garbage company, Mr. Mellows?”

“Yes! It was a hoot.”

“A hoot? Garbage?”

Mr. Mellows ambles back to the print, rubs his index finger along the top of the frame and winks at the farm girl.

The reporter looks annoyed.

“Oh, it’s kind of silly, really. I was just out of college. That was just over forty years ago. The local government wanted to put a county dump – a landfill – in a large field in a posh neighborhood. They said everyone needed to pay their dues. Land filled with crap and germs and ugliness is what they meant. I hate euphemisms, don’t you?”

“I guess so.”

“Well, when I read about the landfill in the news, when newspapers were still in hardcopies, I convinced several families in the neighborhood to start a garbage business, to take advantage of the situation rather than whine about it. I told them they could make money living next to a landfill by picking up trash and dumping it across the street. It would be a local convenience. One fellow had a wooded lot that was just…there…doing nothing but looking pretty…so I convinced him to make it a parking lot for our garbage trucks, which would be camouflaged by trees. I got some investors to go along with the idea and arranged the zoning by calling my business ‘Estate Purification Assistance’.”

Mr. Mellows winks at the reporter, then says in a low voice implying complicity, “The local government interpreted ‘purified estates’ as more valuable than ‘unpurified estates’, know what I mean? ‘Purified estates’ translated to higher taxes, so they had no problem giving us the proper zoning. I guess I don’t hate euphemisms after all.” He pauses. “I disbanded the business after a couple of years although it made money.”

He rubs his right thumb and index finger together indicating it made a lot of money.

“Some people may knock the green stuff, aspire to higher ideals, like poetry or how bugs walk on the ceiling, whatever. Without money…well, nothing’s done and people starve. You might want to write that down too. Money counts.”

“I guess,” says the reporter. He writes ‘money counts’ and follows it with two question marks. He looks at the flickering fluorescent light as if it bothers him.

“Well, young man, it isn’t easy, is it? The idea of interviewing me was more appealing than actually doing it. Right? Am I correct?”

The reporter focuses on the tabletop like a little boy being reprimanded. “No, sir, it’s not so easy. You’re not helping. I mean. Your life is…interesting.”

“Sure is.”

“Amazing is more like it. You make things work, you twist and turn, and there you are at the finish line, smiling and alone. But…who are you, really?”

A siren screams in the street. Mr. Mellows walks to the window and looks below. He sees

mid-day traffic, a few pedestrians, some trash on the sidewalk, a leashed dog pissing against the lamppost, while its owner, a middle-aged Chinese woman, looks the other way. Mr. Mellow turns to the reporter, straightens with resolve, ignores the radiating nerve pain down his right leg due to spinal stenosis, returns briskly to the table and sits down.

“Let’s go on. I promised you an interview and an interview is what you will get. Who am I? I told you. I am Mr. Mellows, a self-made man with a self-made name. I carved my way through life, like a sculptor. Do you understand? Each time a chess piece moves, the game has a new structure, the opportunities are not the same. I am the chessboard. The pieces are my life. I am the substrate for the game. The game cannot be played without me. Without the chessboard, without me, the pieces would have no place to move. Without land, architects couldn’t build houses, without air, pilots couldn’t fly planes, without nature, scientists couldn’t discover anything. The medium is everything. Do you understand that?”

“No, sir, not really.”

Mr. Mellow looks at the fluffy clouds above the aspens in the print.

The reporter writes ‘chessboard, medium is everything’.

“After the garbage, I mean ‘Estate Purification Assistance’ business, I was asked to be an advisor for the state government on urban planning. I thought it strange since I had no credentials in that area, but they told me the concept of merging sanitary engineering, as they called my garbage business, with the suburbs was brilliant. Before I knew it, I was on the zoning commission, planning changes in traffic patterns, designing recreational facilities at the junctions between urban and suburban areas, joining different lifestyles as it were, and so on and so forth. I was given a green medal when I decided to leave after a couple of years.”

“Why green? Do you mean for energy conservation?”

“Maybe. The bronze part dangled from green cloth.”

“What did you do then?”

“Good question. I always had a weak spot for science, I guess because of my father, but mainly I saw it as another way to make a buck. I figured I could get support for anything scientific if people thought they would benefit from the results. They forget about the gap between the science and the reality of having it be useful.”

He glances at the farm girl. “If only she were real.”

Mr. Mellows continues.

“Anyway, I thought I would challenge myself and start a biotech company. I didn’t know any medicine or molecular biology or fancy stuff like that, but I knew people dreamed of cures to nasty diseases, everlasting life and eternal happiness. And that’s what biotech was for me, at that time, anyway: promises. I didn’t pick a stereotypical problem like cancer or blindness or diabetes. No sir. Those obvious areas were overcrowded. Competition’s a nuisance. I wanted to solve everyday issues that people didn’t realize were problems. I settled on a rather silly idea when I think of it now, but it worked, however not as I expected it to. Life is full of curve balls. I wanted to make sweat smell good, appealing, sexy. I know one can simply put on cologne or perfume, but I figured people would like to find a way to make their own sweat appealing rather than cover it up. Vanity, you know. I got $50,000,000 of venture capital from the Miss Universe Foundation, and I established a company in Florida, where they sweat a lot. That was good for another $10 million. At first, I called my company ‘Sniffme’.”

“What happened?”

“Never touched the market I targeted. Had to change the name. Too bad. I liked it. My group of researchers busted their collective ass to find a chemical that could be ingested to make sweat produce a sweet aroma, but nothing really caught on.”

“So, you lost money?”

“Of course not! We came up with a cream made from crushed cranberries, or was it strawberries? Whatever. Anyway, it attracted lobsters. Lobsters are a big industry in Florida. Do you know that lobsters have noses? Well, I didn’t either, but they do, and they are attracted to good smells, good for them that is. We caught them by the thousands and made a ton of money since everyone loves to eat them. I changed the name of the company to ‘Taste’em’. I met a scientist who spent his whole life studying lobster noses and he never made a cent. Actually, he begged for money to continue his research by writing grants all the time. Scientists are weird that way. I always went where the money is rather than try to have the money come to me. You can write that down too.”

“Yes, sir,” said the reporter as he jotted down ‘went where the money is’.

A musical sound distracts Mr. Mellows. He reaches into the inside pocket of his suit jacket that is hanging on the back of his chair.

“Hello,” he says into the cell phone. “Senator Birch’s office? I’ll wait.”

He excuses himself and walks to the far end of the room.

“Yes, Senator, this is Mr. Mellows. Good to hear from you. It was such a pleasure having lunch with you last month. No, no, I have all the time in the world. You’re not disturbing me in the least. What’s on your mind?”

Silence, except for the low rat-a-tat-tat of syllables flowing from the receiver, and the “uh-ha, yes, umm, interesting, ahh, yes, of course…. hmmmmm, absolutely,” uttered by Mr. Mellows.

The reporter waits, looks around and fixates on the print on the wall. His pupils dilate. He puts down his pen, leans back in his chair and smiles. He looks relaxed for the first time.

“It’s a wonderful idea, Senator. Increasing the visibility of steel will certainly harden the resolve of the American people. You can rely on USC. We must not let terrorism frighten us. Steel is impenetrable, resilient, shiny, strong. It says don’t mess with me. A model suburban showcase of steel houses with built in steel furniture powered by the steel-grass lawn says, ‘Bring industry back to America’. What an idea! The houses will be bomb proof, tough as…as…won’t need repairs. Yes sir, with your support and taxpayers’ money, we can do it. What’s that? You need cost estimates and a slogan before the President writes his campaign speech next week? No problem. Consider it done. And thank you sir, for your confidence, support, for your great idea. It’s an inspiration. America owes you a debt. How about lunch next week, sir? Oh, of course, of course, I understand. We’ll lay low. Until later. Bye.”

Click.

“Excuse me for another minute, Bob. That’s correct, isn’t it? Bob? I need to call my deputy.”

Mr. Mellows is alert, as before battle. He calls his office.

“Hello. Stacey, get Karl. Quick. Karl? Cancel all meetings for the next two weeks. I don’t give a royal damn what we agreed on, just listen. Remember the steel family houses? It’s no joke now. Quiet! I told you to listen to me. I’ll tell you more later. Damn it, Karl, you’re working for me. That’s better. Talked to our Senator just now; he swallowed. Who would have guessed? There’s big money here. Get Sam and his crew to come up with blueprints for steel houses in which everything is steel: toilets, tables, chairs, everything. Yes. I know, it’s crazy. Don’t argue. Tell the econ guys to gear up for cost estimates. And we need a catchy slogan. See you within the hour. Don’t breathe a word of this to anyone. I told you things always work out for the best. It’s all about having a positive attitude. You pessimists slay me.”

Mr. Mellows replaces the phone in his jacket pocket. He re-buttons his collar and tightens his tie.

The reporter writes ‘positive attitude, don’t be pessimistic’ in bold letters and underlines it three times.

“Let’s finish up, young man. I’ve got to leave in a few minutes.”

The reporter is quiet, distant. His gaze turns to the print of the girl milking the cow. “She is lovely, isn’t she? I mean the scene and everything,” he says.

“Yes, indeed. Wouldn’t it be nice to live among the aspens, milking cows and chasing butterflies?” answers Mr. Mellows. He looks past the framed print to the dead cockroach on the floor.

“You’re divorced, Mr. Mellows?” asks the reporter.

“Yeah, a long time ago. You married?”

“No, no…not… yet,” says the reporter. “Do you have any children?” he asks.

“A daughter, Cynthia. She has two kids…oops, three. I forgot the little one, almost a year old now. Cute little guy, at least when I saw him six months ago. It’s hard to get time to go to Chicago. Anyway, we must close now. Got your story? Business is waiting.”

Mr. Mellows puts on his jacket and brushes the dust off the lapel.

“What a spot you picked for the interview! Filthy. I hope it’s sold before it deteriorates any more. So, what are you going to say about me?” He looks at his Rolex.

The reporter clips his pen in his shirt pocket. He picks up his notes, pauses and places them back on the table.

“I wrote down what you said, Mr. Mellows.”

The reporter gets up and tucks in his shirt. He walks to the print and stares at the pretty girl. “Beautiful, isn’t she?”

“That’s a bit much, son, but I know what you mean.”

“Thanks for the interview, Mr. Mellows. I can’t begin to tell you how grateful I am for your time, and your insight. It’s been…useful.”

He moves towards the door without his notes.

“Certainly. Not so fast. Will I see the story before it’s published? I don’t want any wrong statements to appear.”

“The story is on the table, sir. I’ve got to go before it’s too late.”

“Wait. Where are you going? Too late for what? Don’t you need your notes?”

“Not where I’m going. I’ve got my eye on this small farm in the country about 100 miles from here, close to where Becky lives. I’m on my way to buy it before someone else has the same idea. It’s a great…opportunity. Becky loves it. Do you know a cheap place around here where I can buy an engagement ring?” the reporter asks.

He goes out the door and begins to walk down the stairs.

Mr. Mellows stands alone in the doorway.

“Charles Melinski,” he shouts to the reporter. “My friends call me Chuck. My parents came from Poland. My mother never climbed trees. She died three years ago.”

The reporter stops and looks back over his shoulder. He smiles. Mr. Mellows is standing still at the head of the stairs, his tall frame bearing down on his right leg riddled with nerve pain.

“Thank you, Mr. Mellows,” answers the reporter as he steps out the front door of the building onto the sidewalk.

Mr. Mellows yells at the top of his lungs, “You’re an optimist, young man! An Optimist, with a capital O!”

A car horn drowns out his voice, and the reporter disappears from sight.

Leave A Comment